New Class Society, Transformation of Hardcore Conservative Base

Where is the LDP’s “hardcore conservative base” now? Where is it headed? The author argues that the only way for the LDP to keep this part of its support base attached is to return to its roots as a “traditional conservative” party. Photo: lost corner / PIXTA

Hashimoto Kenji, Professor, Faculty of Human Sciences, Waseda University

“This book seems to have predicted the results of the Upper House election and the subsequent political situation.” In his highly acclaimed new book, Atarashii Kaikyu Shakai (A new class society), which has garnered much attention, Hashimoto Kenji examines the expanding “underclass” and the transformation of the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) core support base. He also proposes the path the LDP should take.

The shock of the Upper House election results and “A New Class Society”

Nearly a month before the Upper House election on July 20, 2025, I published a book titled “A New Class Society: The End of Widening Inequality Revealed by the Latest Data.” I finished writing the manuscript in February of that year, so the book does not mention the election. Immediately after the election, however, I received inquiries and interview requests from several media outlets asking if the book had predicted the election results and the subsequent political situation.

This suggestion is partly right and partly wrong. In the book, I pointed out that the emerging right-wing parties, Sanseito and the Conservative Party of Japan (CPJ), could gain support by eroding the “hardcore conservative base,” an important part of the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) support base. However, Sanseito’s support far exceeded expectations. I also discussed the future direction of politics after the LDP’s support base eroded, arguing that the LDP might change its approach of catering to the “hardcore conservative base.” However, the political situation remains fluid at present (at least as of mid-August [2025] when this was written), so it remains to be seen whether I was correct. In this article I will explain the present situation step by step.

The expanding “underclass”

It is generally believed that there are four social classes in capitalist societies, which are societies whose primary economic structure is capitalism. The two extremes are the capitalist class, consisting of company managers, and the working class, consisting of employed people. Additionally, there are two middle classes. The new middle class is somewhere between the capitalist and working classes. The old middle class consists of independent and self-employed people in agriculture, commercial, and service industries.

However, changes have occurred in recent years. These changes are due, on the one hand, to macro-level changes, such as economic globalization and the shift toward a service economy; and, on the other hand, to the dramatic increase in non-regular employment due to neoliberal economic and labor policies. Non-regular workers have long existed, but most of them worked as such only for a certain period of their lives, such as part-time students, part-time housewives, or contract workers after retirement. Since the 1990s, however, the number of people who have become freeters[1] after failing to find regular employment after graduating from school has increased. So has the number of people entering non-regular employment through various routes. These people form a poor class with unstable and low incomes, or a potential poor class.

Until recently, the working class was viewed as a unified group, one of two major classes in capitalist societies alongside the capitalist class. However, differences in employment status have created large disparities within this class, effectively splitting it into two. The upper class consists of those in regular employment. Those in non-regular employment will be called the underclass. A “new class society” is one in which the underclass has grown to become one of the major classes.

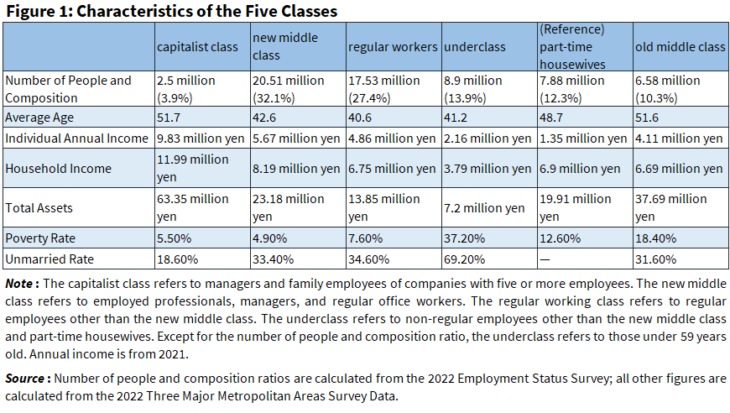

Figure 1[2] illustrates the characteristics of the five classes, which are based on data from the 2022 Survey of the Three Major Metropolitan Areas. However, the numbers and composition ratios are taken from the government’s Employment Status Survey. Most part-time housewives are married female non-regular workers who rely heavily on their husbands, who belong to the new middle class or regular working class, for their livelihoods. Therefore, this stratum cannot be considered an independent class and is treated separately.

At first glance, this figure clearly shows that the underclass is in a distinctly different and more difficult situation than the other classes. The average annual individual income is 2.16 million yen, and the average annual household income is 3.79 million yen. The poverty rate is 37.2%. The unmarried rate is also extremely high, at 69.2%. For economic reasons, many people find it difficult to get married or have and raise children.

The expansion of the underclass is the primary cause of the growing wealth inequality gap in Japan, which has been widening since around 1980. If this issue remains unaddressed, a large elderly poor population will emerge and face many hardships. Furthermore, the underclass continues to grow, primarily among young people unable to find stable employment after graduating from college. If this trend continues, the decline in the birthrate and the aging population will not stop. The total fertility rate is expected to fall to 1.20 by 2023. It must be said that Japanese society is currently facing a survival crisis.

Political Conflict and Five Types of Political Attitudes

As the widening gap in inequality became more widely known and the phrase “society of disparities” became a buzzword, the issue shifted from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in 2009 amid widespread public attention. During this period, inequality was undoubtedly a central political issue. Since then, however, it has receded somewhat into the background due to increased interest in disaster prevention following the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011; the LDP’s return to power in December 2012; the national security legislation[3] that divided the nation under the second Abe Shinzo administration; and the recurring “politics and money” debate. Nevertheless, inequality remains a significant political issue.

However, a new political issue appears to be gaining importance in Japan today: xenophobia. This ideology views China, South Korea, and Chinese and Korean residents in Japan as enemies, and it resents the influx of immigrants. The term “hardcore conservative base,” which emerged around 2022, encompasses xenophobic beliefs alongside traditional conservative ideals such as constitutional reform and military expansion. In other words, since the term includes xenophobia, it has already become an element of conservatism.

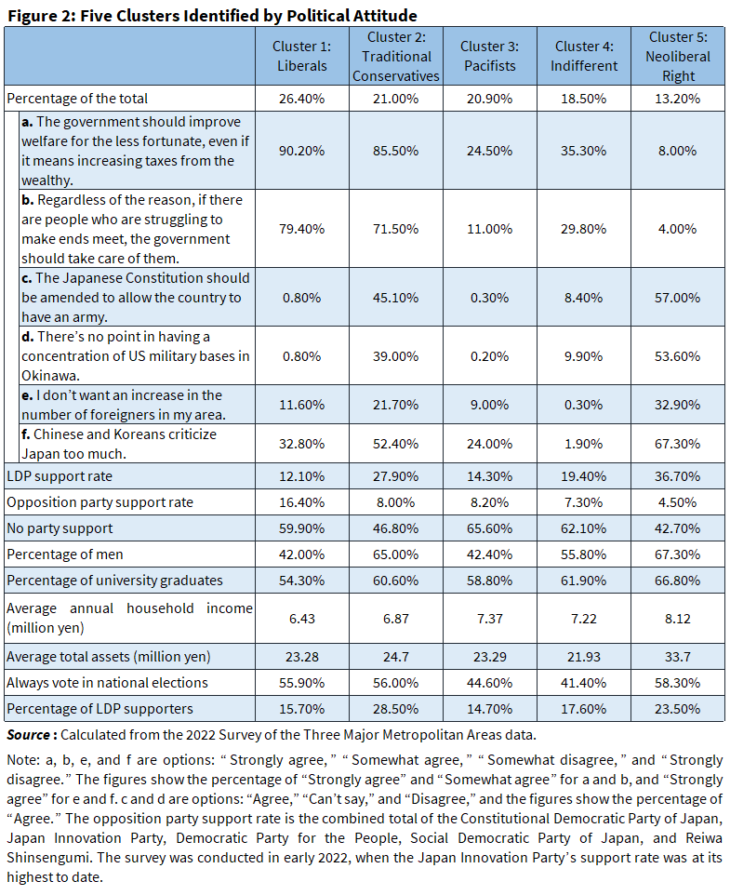

In other words, there are three major political issues in modern Japan. The first is the constitution and security, both of which are key issues in postwar conservative reform. The second is inequality. The third issue is xenophobia. The 2022 Survey of the Three Major Metropolitan Areas included questions about these three issues. While people’s attitudes toward these issues are somewhat interrelated, they are also independent. Using cluster analysis, we categorized people’s political attitudes and identified five highly distinctive clusters. Figure 2 shows the characteristics of each cluster. The cluster analysis used six questions: a through f. Questions a and b evaluated income redistribution policies that reduce disparities. Questions c and d evaluated constitutional reform and the Japan-US security system. Questions e and f evaluated xenophobia and anti-China/anti-Korea sentiment.

Cluster 1 is the largest, accounting for 26.4% of the total. Support for income redistribution is high, while support for constitutional reform and acceptance of the concentration of US military bases in Okinawa are both low. They take a typical postwar reformist stance, and they can be summed up in one word: “liberal[4].” Support for the LDP is low at 12.1%, while support for the opposition parties (Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan [CDPJ], Japanese Communist Party [JCP], Democratic Party for the People [DPP], and Reiwa Shinsengumi) is somewhat higher at 16.4%. However, approximately 60% do not support any political party.

Cluster 2 is the second largest, accounting for 2.0% of the total. While the percentage of people who support income redistribution is second only to “liberals,” nearly half support constitutional reform and nearly 40% approve of the concentration of US military bases in Okinawa. These individuals maintain a postwar conservative stance yet show compassion toward those living in poverty. They can be called “traditional conservatives.” The LDP has a high support rate of 27.9%, but support for other parties, such as Komeito and the Japan Innovation Party (JIP), as well as opposition parties, is also high at 25.3%. This means the LDP is not the only party in the group.

Cluster 3 accounts for 20.9% of the total. Although the percentage of people who support income redistribution is low, those who “do not really agree” are not extremely opposed. Notably, almost no one supports constitutional reform or the concentration of US military bases in Okinawa. These groups share the same postwar reform stance as “liberals,” but differ in that their attitude toward income redistribution is unclear. It would be more appropriate to call them “pacifists.” Support for the LDP was second lowest at 14.3%. Support for the opposition parties was slightly higher at 8.2%. However, 65.6% of voters did not support any political party, accounting for nearly two-thirds.

Cluster 4 accounts for 18.5% of the total. This cluster is characterized by a lack of clear stance. Responses to questions about income redistribution, security, and xenophobia tend to be “somewhat agree,” “not really agree,” or “can’t say.” This suggests that they are not particularly interested. As expected, few people have a party affiliation; 62.1% do not. Let’s call this group the “indifferent group.”

Cluster 5 is the smallest, accounting for only 13.2 percent of the total. The proportion of people who support the redistribution of income is extremely low, at just a few percent. In contrast, a majority of people support constitutional reform and the concentration of US bases in Okinawa. Furthermore, these groups exhibit unusually strong xenophobic tendencies. These people support traditional conservative positions but also have strong xenophobic tendencies and reject income redistribution policies. They can be called the “neoliberal right.” Support for the LDP is high, at 36.7%, while support for opposition parties is low, at just 4.5%.

The True Nature and Political Influence of the “Neoliberal Right”

The “neoliberal right” is probably the true essence of the so-called “hardcore conservative base.” What kind of people are they? Over two-thirds of them are men (67.3%), and a high proportion of them are university graduates (66.8%), far exceeding the other groups. Their annual household income is 8.12 million yen, and their total assets are 33.7 million yen. These figures far exceed those of other groups, making their wealth conspicuous.

Furthermore, the “neoliberal right” has the highest proportion of people who say they always vote in national elections. Though they are a small group, they account for 23.5% of LDP supporters, nearly as many as the larger “traditional conservatives” (28.5%). Because their voter turnout is higher than that of the other clusters, they should account for an even larger proportion of the LDP’s votes.

Although the LDP’s main supporters are “traditional conservatives” and the “neoliberal right,” the party leaned closer to the “neoliberal right” after losing power in 2009. This continued through the Kishida Fumio administration, which followed former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s term. While implementing a series of security measures opposed by many, the LDP took a passive stance toward eliminating inequality and income redistribution. During this period, the LDP favored the “neoliberal right,” a minority group. In a sense, the LDP was taken over by the “neoliberal right.”

As a result, “traditional conservatives,” who should have been the LDP’s base of support, have been forced to make a difficult choice. They want constitutional reform, but the LDP panders to the “neoliberal right,” is passive about income redistribution, and allows inequality to widen. Therefore, despite their dissatisfaction, they had no choice but to vote for the LDP or another party.

The LDP should return to being “traditional conservatives”

But what would happen if a party further to the right of the LDP were to emerge? This was partially evident in the 2024 Lower House election results, when some of the “hardcore conservative base” abandoned the LDP and voted for the new right-wing parties, Sanseito and the CPJ. This trend became even more widespread in the recent Upper House election.

However, this does not seem to be the only reason. In the proportional representation district, Sanseito received 12.5% of the vote. Combined with the CPJ, this figure rises to 17.6%. Support for the “neoliberal right” alone cannot explain such a surge. It is likely that Sanseito’s voters were not only politically conscious “neoliberal right” voters but also those who are less politically conscious and simply “hate xenophobes” or those who oppose income redistribution.

The DPP also made great strides, receiving 12.9% of the vote. Who voted for the DPP? It was likely “traditional conservatives.” In other words, the LDP government distanced itself from Abe’s policies that catered to the “neoliberal right.” However, the LDP stopped short of implementing income redistribution policies to stop the growing wealth gap. As a result, the LDP was abandoned by both the “neoliberal right” and “traditional conservatives.”

This election revealed a trend of emerging right-wing parties garnering support from the neoliberal right. This trend is unlikely to stop anytime soon. The reason the LDP has been able to garner support from the “neoliberal right” until now is simply because there has been no powerful party to the right of the LDP.

In contrast, while voters are divided on security issues, the majority want to reduce inequality. Therefore, if the LDP wants to remain a ruling or similarly influential party, it must regain the support of “traditional conservatives” by proposing policies that reduce inequality through income redistribution. This shouldn’t be too difficult. This is because, for a long time after the war, while the LDP advocated constitutional reform and maintaining the Japan-US military alliance, it was also a party that prioritized the weak, protecting the interests of small and medium-sized enterprises and self-employed people.

Although conflict over constitutional and security issues would continue, if the LDP were to shift its stance, agreement would be reached on reducing inequality and eliminating poverty through income redistribution. This would improve the situation of the underclass, ensuring that everyone has enough income to reproduce and restoring the birthrate. Increased consumption would stabilize the economy and eliminate concerns about the collapse of the social security system. Furthermore, important political issues such as the constitution and foreign policy would no longer be dominated by a few people’s views. A healthy political society would emerge, one in which different positions are represented fairly and dialogue is fostered.

For the LDP to survive, it must break away from the Abe line and return to its origins as a “traditional conservative” party.

Translated from “Atarashii Kaikyu Shakai, Ganban Hoshu no Tenkan (New Class Society, Transformation of Hardcore Conservative Base),” Voice, October 2025, pp. 206–213. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [January 2026]

[1] The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “White Paper on Labor Economics” (2003) defined this group as graduates aged 15 to 34 (unmarried women only) who are either employed as “temporary workers or part-time workers” or unemployed, not engaged in housework or attending school, and who desire temporary or part-time work (unemployed persons). The Ministry estimated the number of people falling under this category to be 2.09 million (2002).

[2] The survey was conducted online from January to February 2022. The target population consisted of residents aged 20–69, with 43,820 valid responses collected. Note that the portion of the underclass aged 60 and over includes individuals who worked as regular employees for many years before becoming non-regular workers through re-employment. Since their annual income and total assets are not low, they were excluded from all calculations except for headcount and composition ratio.

[3] The Legislation for Peace and Security refers to a series of security-related bills enacted in 2015, including the authorization of the exercise of the right of collective self-defense. Along with the three key security documents the National Security Strategy, National Defense Program and Defense Buildup Program, it is positioned as the foundation of Japan’s security policy.

[4] In Japan, the term “liberal” has been used by politicians and the media to mean non-conservative and non-communist from the 1980s.

Keywords

- Liberal Democratic Party

- hardcore conservative base

- underclass

- widening inequality

- new class society

- security

- xenophobia