Land and Homes and the Japanese: The dream of “My Home” ownership for the masses—The reality of inheritance by the elderly requires a fluidization policy

Hirayama Yosuke, Professor, Kobe University

Prof. Hirayama Yosuke

The popularization of home ownership characterizes the social changes in postwar Japan. The homeowner society was formed when the middle class expanded and more people lived in their own homes as a consequence of spectacular economic growth. Many people enjoyed stable employment and income, and moved from rented housing into their own housing. Aiming to form a society based on promoting home ownership, the government, which formulates and implements housing policies, focused on driving the expansion of the owner-occupied housing sector. It was thought that facilitating home ownership would not only improve housing conditions, but also stimulate economic growth and encourage social integration.

The spread of home ownership into wider segments of society is a phenomenon that became viable under the specific socioeconomic conditions characteristic of the latter half of the twentieth century: population growth and a youthful demographic, increases in marriages and household formation, demand for housing and expanding home construction, strong economic growth, stable employment and income, the formation of a massive middle class, and national support for expanding home ownership. In this context, the phrase “My Home” (my own home), which was used during the period of rapid economic growth not only signified home ownership; it was also based on stable employment and income and had the image of supporting marriage and child-rearing.

When the population and the economy entered the post-growth phase in the 1990s, the relationship between housing and social formation changed in fundamental ways (Hirayama and Izuhara, 2018). Home ownership came under siege by new factors such as depopulation and a low birthrate coupled with an aging population, fewer marriages, a rise in unmarried and single individuals, a decline in housing demand and construction, minimum or negative growth rates, insecure employment and income, a shrinking middle class, and reduced state support for housing. Reflecting the socioeconomic conditions in the new century, the term “my home” is now used less frequently.

This paper focuses on how the homeowner society in the post-growth period differs from the latter half of the twentieth century. In particular, we look at the connection between home ownership and social stratification. In the period of demographic and economic growth, many households climbed the housing ladder by moving from rented housing to their own housing. This flow was amplified by the constant rise in the middle class who lived in their own homes, creating an image of more equality. However, in the post-growth phase, changes in the flow and stock related to home ownership have become new drivers for stratification. The flow of households climbing the housing ladder is sluggish and, at the same time, the distribution of the large volume of accumulated housing stock has become more inequal, creating a new mechanism for increasing inequality. Neglecting such stratification is damaging social stability. As a difficult issue that is both challenging and worthwhile, the question of how to reduce inequality stands in the way of society. Below, I will discuss how the changes in the family-owned housing sector are related to a new structure that creates social stratification. I will also spell out that the approach of the housing sector will be important for dealing with inequality among people (Hirayama, 2020).

Home Ownership Rate Among Young People and the Older Generations

The ratio of owner-occupied households, which has been roughly 60% since the late 1960s, has barely changed, but the composition of the family-owned housing sector has changed. It is characteristic of post-growth society that the flow of home ownership by young people is shrinking and the housing stock of the older generations is increasing.

The home ownership rate of the young generation has declined. From 1983 to 2018, the ratio of owner-occupied households dropped significantly from 45.7% to 26.3% for households where the head is in the 30–34 age bracket. The home ownership rate has also fallen from 60.1% to 44.0% in the 35–39 age bracket.

The primary reason for the reduced rate of home ownership by young households is that marriage rates are on the decline. According to the national census, 21.5% of men and 9.1% of women in the 30–34 age bracket were unmarried in 1980, but by 2015, the figures were remarkably high at 47.1% and 34.6% respectively. The rate of unmarried young people has not changed greatly since the start of the twenty-first century and remains high. In Japan, home ownership and family formation are closely connected, and the majority of people do not buy a home before getting married. There is a direct link between the increase in the rate of unmarried young people and the fall in the rate of home ownership.

Secondly, insecure employment and income has caused a decrease in attaining home ownership. Since the 1990s, the government has relaxed labor regulations, which has brought about an increase in irregular employment. As a result, there has been a marked rise in insecure employment for the young. Even among those who are in regular employment, home ownership levels have been stagnating or decreasing.

Thirdly, the home ownership economies have changed. In the 1980s when the real estate bubble expanded, the price of housing and land continued to increase due to the inflation economy making it difficult to attain home ownership. In the post-bubble period (1995–2015), home and land prices slumped while mortgage rates remained low in the deflation or disinflation economy. Nevertheless, real income declined and the real burden of mortgages increased, making it even more difficult to purchase a house. Home ownership was linked to the accumulation of real estate assets. People were looking to own their homes for economic reasons, but the real estate prices declined in the post-bubble period, undermining the security of home ownership as an asset. The burden of a housing purchase increased while the asset value turned uncertain. This turned into a factor that kept young households out of the home-ownership markets.

To understand the housing situation for the young generations, we need to focus on the differences between generations as well as stratification within generations. For young people, the reality is that there is a clear correlation between family, work, and the housing situation. In many cases, marriage and child-rearing are supported by stable employment and income followed by attaining home ownership. In this regard, the unmarried rate is high and the home ownership rate is low among those who are in insecure employment. In the parent generation, most people had it all, including stable jobs and income, a spouse and a family, and home ownership. There is still a group that has it all, but there is an emerging and expanding group that has nothing among the young generations.

Meanwhile, the housing stock owned by the elderly has increased significantly in step with the maturation of the homeowner society. Even though the home ownership rate among young people is falling, the rate has remained constant across all households because home ownership by the elderly has increased. The home ownership rate is at a high level of around 80% with the number of owner-occupied households where the head of the household is sixty-five or older increasing six-fold from 2.46 million to 15.33 million in the period from 1983 to 2018.

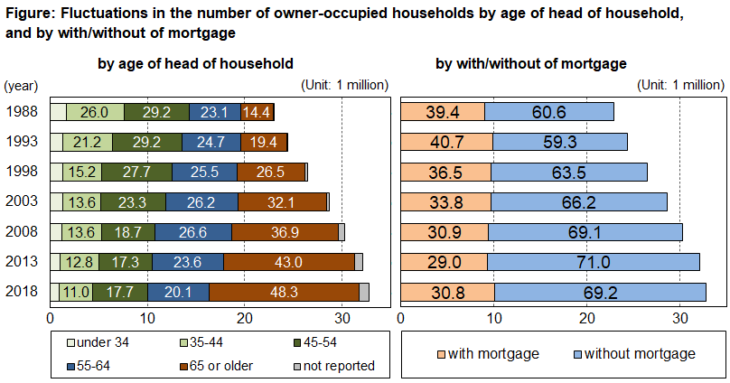

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the homeowner society was distinguished by its youthfulness and “my home” was the place where young couples raised their children. The mature homeowner society of the new century is characterized by its elderliness. (Fig.) Owner-occupied households where the head of the household is forty-five or younger have dropped from 33.3% in 1988 to 13.9% in 2018, whereas households where the head is sixty-five or older have risen from 14.4% to account for nearly half (48.3%). Meanwhile, households where the head is among the latter-stage elderly (seventy-five or older) have increased from 4.3% to 22.7%. The composition of the homeowner society, which was focused on “my home” for young households, has changed dramatically. In the post-growth period, many owner-occupied homes have, as it were, become “housing for the elderly.”

Note 1: The figure illustrates the results of the Housing Survey and the Housing and Land Survey. The percentage of respondents with or without mortgages is proportional to the percentage of respondents with or without loans identified in the National Consumption State Survey and the Survey of Family Income, Consumption and Wealth (name changed from the National Consumption State Survey in 2019) conducted in the year after each survey year.

Note 2: Excluding the unspecified, the figures in the diagram are composition ratios. Source: Created based on housing statistics survey reports, the Housing and Land Survey, the National Consumption State Survey, and the Survey of Family Income, Consumption and Wealth

Is It Sustainable to Rely on Mortgages?

The intergenerational differences in home ownership are related to a trend for an increase in outright home ownership and a stagnation in mortgaged home ownership. Outright ownership refers to a debt-free state where the mortgage is fully paid or home ownership has been attained without a mortgage. Mortgaged home ownership indicates a house with outstanding mortgage debt. The average home ownership rate has barely changed, but when home ownership is categorized by presence or absence of debt, it is clear that the balance between outright and mortgaged home ownership has changed.

In 1988, the ratio of owner-occupied households with mortgages was 39.4%, but since 2008 the ratio has hovered around 30% (Fig.). This corresponds to a decline in the home ownership rate for young people. On the housing ladder, mortgaged home ownership occupies the middle rung between rented housing on the lower rung and outright home ownership on the upper rung, a “cornerstone,” as it were, of a system that helps people move into the owner-occupied sector. The stagnation in mortgaged home ownership suggests that an increasing number of households are stuck on the lower rung without the means to reach the middle rung, and that it is even more difficult to transfer to the upper rung.

The government developed housing policies to promote home ownership not only as a means to improve housing conditions, but also as an economic policy. The main method was to provide mortgages. Since the start of the period of low growth in the 1970s, the government has tried to stimulate the economy by expanding the provision of the Government Housing Loan Corporation’s mortgages every time there is an economic downturn. The Corporation was abolished in 2007 within the context of the policy to reform various government-affiliated corporations. However, tax breaks on mortgages and other measures to promote home ownership have been continued.

As Wolfgang Streeck (2014), the German sociologist, has pointed out, the focus of policy measures in developed countries to deal with declining growth rates has shifted from national debt to personal debt since the economic crises in the 1970s. The government has issued a series of bonds to stimulate the economy through public-works projects. This was followed by measures to promote personal borrowing rather than government borrowing. The flagship policy is the expansion of home ownership based on mortgages. Colin Crouch (2011), the British political scientist, refers to the method of increasing individual mortgage debts to stem the slowdown in growth as “privatized Keynesianism”. Whether a policy of increasing individual debt is sustainable is another question. When Japan entered the post-growth phase, it became increasingly difficult to develop economic policies that rely on personal debt due to demographic and economic stagnation. This is made evident by the lack of growth in mortgage home purchases and the trend for lower home ownership rates among young people.

Outright Home Ownership Increases

Meanwhile, outright owner-occupied households form a large group that has increased from 60.6% of all households in 1988 to 69.2 70% in 2018 (Fig.). The primary factor is the aging demographics. Many households have bought homes with mortgages, continued repayments, and eliminated the debt by the time they reach old age.

Outright home ownership provides a real estate asset that increases the security of the elderly since the burden of housing costs is light. For the super-aged society to remain stable, an important key factor—which is mostly overlooked—is that the majority of the elderly own and occupy a debt-free home. In the homeowner society, social security and other systems are implicitly designed around the assumption that the housing costs of the elderly will be light. Measures to keep pension payments at low levels are feasible if most of the elderly live in a home that they own outright. In that sense, outright home ownership functions as a “self-pension” or “private social-security.”

In 2019, the Working Group on Capital Market Regulations of the Financial System Council at the Financial Services Agency caused much debate when their preliminary calculations showed a twenty million yen shortfall in funds to cover thirty years of post-retirement life. It is not the discussion itself that must be noted here, but the household model that formed the basis for the calculations. The Working Group looked at elderly households where household expenses related to housing do not exceed 5.5% of all expenses, which is less than, for example, utility costs (8.2%). Analyses of the household economy for the elderly take it for granted that the elderly live in homes they own outright and thus benefit from a “self-pension.”

In a society that is premised on promotion of outright home ownership, the elderly in the rental sector are suffering a crisis of security. In the case of private rented housing, in particular, the houses are small, the facilities are old, and the tenants are at risk of eviction. In addition, the heavy rent burden reduces pension benefits and accordingly undermines economic security. As is evident from the preliminary calculations of the Working Group on Financial Markets, most analyses of policies for the elderly hardly ever consider the situation of the minority who live in rented housing. There are acute differences in security levels between those in the older generation who own their homes outright and those who do not.

Wealth or Waste?

In the post-growth homeowner society, unequal distribution of the accumulation of housing stock and asset values causes stratification. Thomas Piketty’s (2014) theory of social inequality has drawn attention from a wide range of fields including housing research. According to Piketty, the inequality of capital ownership is greater than the inequality of labor income. This trend becomes obvious when the economic growth rate decreases. In the postwar period of high economic growth, capital ownership inequality shrank because capital had been destroyed in the war, while the increase in labor incomes raised equality levels. In comparison, since the 1980s when the growth rate declined, inequality has increased due to differences in the accumulation of postwar capital ownership between households and a decline in the labor income growth rate. Piketty’s argument suggests that we need to pay attention to the distribution of housing assets as a key factor that makes post-growth society more unequal.

In Japan where the population and the economy have stagnated, “the instability and uneven distribution” of housing asset values is a central cause of social stratification. Even though the population is decreasing, the housing supply continues to increase and housing vacancy rates are rising. Increasing the uncertainty, the economy has gone through upheavals from the long stagnation of the post-bubble period after the collapse of the real estate bubble (early 1990s), the mini-bubble period in the major cities (2006–2007), the world financial crisis (2007–2008) to the period of extraordinary monetary easing (2013–). The demographic and economic changes have made the value of housing assets less secure and their distribution more uneven.

As a result, the spatial and temporal divisions in the housing market have deepened. Whereas one household may be wealthy because the market assessment of their housing rises, the assessment of the housing of another household continues to drop. In addition, “wasted” vacant houses that only impose a management burden on the owner have increased. Households that bought a home at the peak of the bubble economy have suffered large-scale latent losses because of the subsequent housing deflation. Trends on the housing market have become differentiated in Tokyo, other major cities and smaller cities. In Tokyo, house prices are rising due to unprecedented monetary easing and households that bought their homes after the world financial crisis have gained latent profit. In small cities, house prices continued to fall even in the period of the mini-bubble and monetary easing, and the number of abandoned vacant properties has increased. In the post-growth period, temporal and spatial fragmentation in the housing market has divided housing assets into wealth and waste, forming a new structure for social stratification.

Accumulating, Dissipating, Renting

In the latter half of the twentieth century, owner-occupied homes were the property of independent households. Young people who had moved from rural areas to the major cities liberated themselves from their own families, regions, and social classes and tried to buy their own homes. The group that climbed up the housing ladder grew larger and the middle class expanded, which was assumed to increase the degree of equality. In contrast, how a multi-generational family forms and uses its housing assets in the post-growth society where housing stock is increasing has created a new structure of social inequality.

The home is not only the property of the resident household, but it is also a family asset that is passed onto the next generation through inheritance. In a mature society, the home ownership rate is high in the parent generations, and since there are few siblings in the offspring generations, more children will inherit the parental home. Moreover, as the housing stock increases, more households will own additional properties in addition to the home where they reside. These additional properties are used as residences for family members, or put on the rental housing market. In addition, parents are increasingly supporting their children’s households with home purchases. As a part of its economic policies, the government has expanded tax breaks on cash gifts by living parents to their offspring to support the purchase of their own home.

In post-growth society, the offspring generations are not necessarily independent in terms of obtaining and owning homes and their asset values. Factors such as the kind of house the parent owns, whether there will be an inheritance, and whether the parent can support a housing purchase have an increasing impact on the housing asset situation of the offspring generation.

Housing assets transcend the concerns of the household. They are an object of management for multiple generations of a family, creating a new form of hierarchy (Forrest and Hirayama, 2018). In the upper echelons of society, there are “accumulating families” who increase their wealth by transferring housing assets from the parent generations to the offspring generations. High income earners among the offspring generations will have acquired their own high-value homes, bought real estate in good locations as investments, and they will also inherit large-scale housing assets from their parents. Some of the plentiful housing assets are put on the market, bringing in rental income. Families with knowledge and information of the real estate market will profit from buying and selling homes. In the lower ranks of society, there are families who dissipated their gradually diminishing housing assets. Offspring households who do not have such a high income buy houses where the location and other conditions are less than satisfactory, so the asset values are not secure. If they have moved to a major city from a small regional city or an agricultural community, they may inherit their parents’ house, but the market for selling or renting is nearly non-existent and many homes go to waste as vacant houses. In even lower strata of society, there are perpetually renting families where both the parent and the offspring generations continue to live in rental housing. In a homeowner society, policy support for the rental sector is held at a minimum, so multiple generations of families who do not own their own homes are faced with housing difficulties.

Socializing Intergenerational Transfers of Housing Stock

Private ownership will remain the dominant form of home ownership in the near future. In this sense, the homeowner society is sustainable. But it has changed. When demographics and the economy enter the post-growth phase, the mature homeowner society is gradually stratified. As previously mentioned, there are intergenerational differences in housing conditions. Stratification within generations has also advanced. In addition, housing conditions for multi-generational families have become stratified.

The housing policies in the latter half of the twentieth century were aimed at expanding the family-owned housing sector. It was thought that increasing the number of homeowner households would create a middle class and support social stability. However, in post-growth society, the flow of people climbing the housing ladder has stagnated while the housing stock has increased. Therefore, it is necessary to formulate and implement housing policies that will mitigate stratification among people.

In addition to supporting the expansion of home ownership, a policy that aims to improve the rental sector is particularly important. It has become more difficult for young people to buy their own homes. Many households in the older generations live in their own homes, but the situation is extremely insecure for the minority who are tenants. There is no longer any basis for the assumption that most people will buy their own homes. It is increasingly necessary to build a tenure-neutral housing policy.

Furthermore, there are questions about the nature of intergenerational transfer in a society that has accumulated housing stock. Family inheritance is the main route for transferring the housing assets of the older generations to the next generation. This does not necessarily improve housing for the young generation. Life expectancy has increased and the heirs are often getting older when the inheritance occurs. Therefore, many people in the offspring generations who inherit the housing assets of the parent generations are no longer young, but an older generation. Although the housing assets are transferred to the offspring generations, the outcome is that the inheritance stays with the older generations. In addition, many elderly people are unable to use the inherited housing and are forced to leave the houses vacant.

This situation implies the need to “socialize” the intergenerational transfer of housing stock by closing down the family route and using market and government routes. The existing housing market remains underdeveloped and small-scale. It needs to be developed to mechanisms of promoting and stimulating intergenerational transfers of housing wealth via the market route. Policies for using existing vacant houses and expanding the supply for low-income earners are required in the government sector. Such measures have already been launched, but as of the present, there has been very little success. Large-scale measures to use existing housing for people who experience housing difficulties should be developed. The mature homeowner society has accumulated a large quantity of housing stock. How to combine the government, market and family routes and what methods to use to pass the stock to the next generation in an appropriate fashion are important issues to consider.

Inheritance via the family route was an asset under the patriarchal system in prewar rural society. At the time, home ownership in urban areas was a privilege of a very small section of society. In the new postwar society, home ownership by independent households became widespread. Farmland reforms dismantled the landowner system and created numerous landed farmers. The popularization of home ownership in urban areas was a similarly important change. Many households built or bought homes, freeing themselves from the landlord through ownership, and setting up independently of their family origins. In the postwar society, your origins did not matter, at least not in principle. This was symbolized by home ownership. However, home ownership in the post-growth period has once again started to show family asset aspects, and the divisions between families who accumulate, dissipate, or rent their homes have been linked to social stratification. Piketty has pointed out that the new inequality in the twenty-first century tends to become entrenched across generations. Certainly, inheritance of occupations, social status, assets, and housing is increasing. We need to go in a direction that supports the creation of a new society where your origins do not matter by formulating and implementing housing policies.

References:

Crouch, C. (2011) The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism, Cambridge: Polity.

Forrest, R. and Hirayama, Y. (2018) Late home ownership and social re-stratification, Economy and Society, 47(2), 257-79.

Hirayama, Y. (2020) Mai home no kanatani—Jutaku-seisaku no sengoshi wo doyomuka (Beyond my own home—How to read the postwar history of housing policy) Chikuma Shobo.

Hirayama, Y. and Izuhara, M. (2018) Housing in Post-Growth Society: Japan on the Edge of Social Transition, New York: Routledge.

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Translated by Yamagata Hiroo, Morioka Sakura and Morimoto Masafumi. Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo.

Streeck, W. (2014) Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, London: Verso Books. (Jikan kasegi no shihonshugi—Itsumade kiki wo sakiokuri dekirunoka, translated by Suzuki Tadashi, Misuzu Shobo 2016)

Translated from “Tokushu ‘Tochi to Ie to Nihonjin:’ Shomin no yume datta ‘mai homu’—Roro-sozoku no genjitsu to motomerareru ryudo-ka seisaku (Land and Homes and the Japanese: The dream of “My Home” ownership for the masses—The reality of inheritance by the elderly requires a fluidization policy),” Chuokoron, December 2021, pp. 48-57 (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [February 2022]

Keywords

- Hirayama Yosuke

- Kobe University

- home ownership

- homeowner society

- “My Home”

- mortgage

- rental housing

- social stratification

- inequality

- inheritance

- depopulation

- birthrate

- owner-occupied housing

- family-owned housing

- employment

- income

- marriage

- pension

- self-pension

- housing stock

- vacant houses

- housing policy

- post-bubble period