Why Are There 180 Different Swimming Strokes? — Exploring Suifu-ryu Suijutsu, a School of Japanese Traditional Swimming

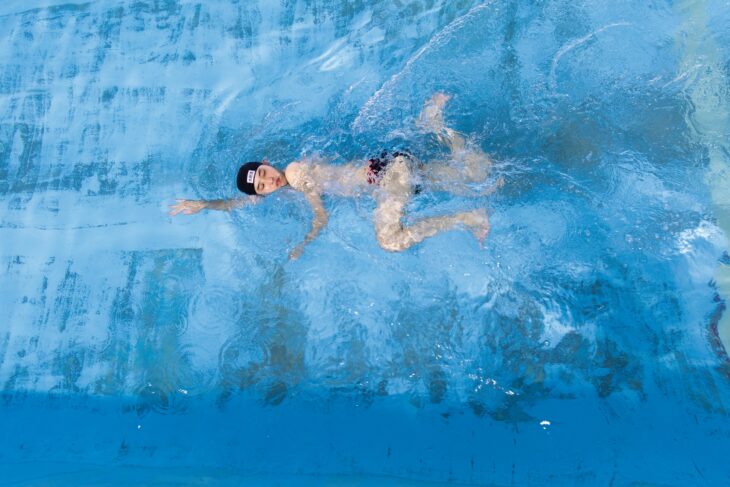

Hitoe-noshi (single sideways kick) is one of the representative swimming strokes of Suifu-ryu suijutsu. The ideal technique is one in which the body does not move up and down, and the swimmer swims with a long, leisurely extension. All photos: Mizkan Center for Water Culture

[Physical Education/Sociology] There are swimming styles that have been passed down through the generations in Japan. Nihon eiho (Japanese swimming techniques) developed in a way suited to the waters of each region, such as rivers, lakes, and oceans. Currently there are 13 schools. We [the editorial staff of Mizu no Bunka] covered the historical background of one of them, Suifu-ryu suijutsu (Suifu school of the Japanese martial art of combat swimming), which is being kept alive in in Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and were shown some of the swimming techniques.

Can be continued for life, regardless of age

Sideways in the water, with the face turned upwards above the surface, the swimmer performs scissor kicks called aoriashi while the lower hand extends forward and pulls down through the water. This is hitoe-noshi (single sideways kick), one of the representative swimming strokes of Suifu- ryu suijutsu, a school of Nihon eiho that has been practiced in Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, since the Edo period (1603–1867).

Hitoe-noshi (single sideways kick): One of the representative swimming strokes of Suifu-ryu suijutsu. The ideal technique is one in which the body does not move up and down, and the swimmer swims with a long, leisurely extension.

The Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association holds weekly Suifu-ryu suijutsu classes for children and adults at the indoor swimming pool in Aoyagi Park on the banks of the Naka River.

Kashimura Koji, of the association, teaches children as the head of the Mito Suifu-ryu Junior Sports Club. Kashimura went to a swimming school to become a competitive swimmer, but gave up when he was in the fourth grade of elementary school. A teacher, who found out that he had given up competitive swimming, offered him a place in the Nihon Eiho Taikai tournament and he began Suifu-ryu suijutsu.

“I was not good at other sports, but I was good at swimming, so I thought I could keep swimming. Nihon eiho is not a time-based sport like competitive swimming. It is a lifelong sport that can be enjoyed by people of all ages. I’ve been doing it for 42 years, but I don’t think I’ve mastered it yet,” Kashimura says with a smile.

The Nihon Eiho Taikai tournament is a scoring competition where Nihon eiho schools from all over the country gather to compete in their swimming kata (form).

The swimming strokes of Suifu-ryu suijutsu are based on noshi-oyogi (squid-style swimming), which can be broadly divided into otai[1] (sideways or sidestroke), heitai (flat, similar to breaststroke), rittai (standing)[2], which is a type of tachi-oyogi (standing swimming or treading water), sensui (diving), and ukimi (floating). If you break it down further, there are as many as 180 different swimming strokes. It’s certainly a school of swimming worth dedicating a lifetime to mastering.

But why are there 180 different swimming strokes? The secret lies in the land and history of Mito.

Suijutsu (combat swimming) was necessary to protect the country

Mito is a castle town with the Naka River flowing to the north, Lake Senba (332,131 square meters) to the south, and the Pacific Ocean not far away to the east. As the kanji for Mito (水戸) indicates, it is a land that is an “entrance and exit point for water.” In addition, in the Edo period, Lake Senba was five times the size it is today. Therefore, people skilled in suijutsu were needed from the Sengoku period[3] onwards to protect the land.

“In those days, there were no bridges, so messengers had to be able to swim in rivers and lakes to perform their duties in battle. Geographical factors were a big part of why swimming developed so long ago,” says Yamaguchi Nobuyoshi, president of the Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association.

In the Edo period, Mito, which became one of the three houses of the Tokugawa[4], was also known as Suifu[5]. The swimming techniques were developed under successive feudal lords, beginning with the first, Tokugawa Yorifusa (1603–1661) and the second, Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628–1701). “The patronage and encouragement of the rulers and the abundance of human resources to teach swimming are also factors that have allowed Suifu-ryu suijutsu to be passed down for so long,” explains Yamaguchi.

Kacchu-oyogi (armored swimming): In Suifu-ryu suijutsu, not only armor and helmets are worn, but also hakama, gauntlets and shin guards, weighing about 20 kg all together. Despite the difficulty, Kashimura demonstrates it beautifully. The reason for swimming with the left side of the body facing up is to avoid dropping the wakizashi (Japanese short swords).

Each of the 180 swimming styles has its own origin and reason. For example, the sideways tagurinoshi is a noshi-oyogi swimming style in which the swimmer swims while pulling on a stretched rope. The standing moro-nukite is a swimming stroke that uses the movement of jumping out of the water to look a little ahead or jump onto the side of a boat, the shore, or a small rock. The conditions of rivers and lakes vary from place to place and change every day— the water may be shallow, the current may be fast, or there might be obstacles floating in the water. Practitioners also had to swim while carrying weapons and baggage. “I think that swimming styles were developed to suit the natural environment and required purpose, changing little by little as they were passed down,” says Yamaguchi.

In a place like Mito, surrounded by bodies of water with diverse environments, it must have been natural for a wide variety of swimming styles to emerge to protect the swimmers and cross the water safely.

Tradition continues at pools, and long-distance swimming competitions are back

Except for a brief hiatus after the Haihan-chiken (abolition of the han system) during the Meiji period (1868–1912) and shortly after the end of World War II, Suifu-ryu suijutsu classes have continued uninterrupted. “Until about 1963, when it became impossible to swim in the Naka River due to water pollution, we taught at swimming venues along the river. At our peak, we had more than 6,000 students at seven swimming venues,” recalls Yamaguchi.

The swimming venues along the Naka River were closed one after the other, at the same time as swimming pools began to be installed in elementary schools. In 1970, a massive outdoor facility with six pools, said to be the largest in the Asia, was completed in Aoyagi Park (Suifucho, Mito City). In the same year, the masters of the major swimming venues joined together to form the Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association in order to pass on Mito’s Nihon eiho tradition to future generations, even though they could no longer practice in the Naka River. Thus, Suifu-ryu suijutsu classes began to be held in swimming pools.

However, swimming in the Naka River did not cease completely. The Naka River Long Distance Swimming Competition, which had been held annually since 1947 under the supervision of five of the swimming venues, was cancelled in 1963, but resumed in 1991 due to improvements in the river environment. The Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association is one of the organizing groups. Participants swim the 3.5 km from Chitose Bridge to Suifu Bridge in a line, using breaststroke and sidestroke.

Arakawa Isami, vice president of the association, says the following about the long-distance swimming competition:

“Many of the participants are students of Suifu-ryu Suijutsu. For safety, instructors who know where the current is deep and fast swim alongside the swimmers and lead the way in a boat. Participants can be as young as fourth grade students, and people in their 80s have taken part. It feels great to look up at the shore and the sky from the surface of the water. It’s a real pleasure you can only understand by swimming in a river.”

In addition to teaching at public pools and elementary schools, the Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association also participates in the Nihon Eiho Taikai tournament and is involved in its management, serving as judges, etc. “Members play different roles and contribute to the spread of Nihon eiho. It’s not just about swimming, it’s also about having a variety of social experiences, which is why it’s a ‘lifelong sport,’” says Yamaguchi.

The place for teaching the next generation has moved from the river to the pool, but long-distance swimming on the Naka River, which began in the Edo period as nagare to-oyogi (long-distance swimming), continues to this day. In addition, traditional Japanese swimming styles, developed to suit different bodies of water and conditions, have been passed down through the ages and are still practiced in each region.

(Interviewed on May 12, 2024)

Translated from “Tokushu Minna Oyoideru? Naze 180 shurui mono Oyogikata ga?—Nihon Eiho no Ichi ryuha ‘Suifu-ryu Suijutsu’ wo tazunete (Special Feature: Is Everyone Swimming? Why Are There 180 Different Swimming Strokes? — Exploring Suifu-ryu Suijutsu, a School of Japanese Traditional Swimming),” Mizu no Bunka, Vol. 77, July 2024, pp. 24–27. (Courtesy of the Mizkan Center for Water Culture™, Mizkan Holdings Co., Ltd.) [October 2024]

Reference: “Tokushu Minna Oyoideru? Naze 180 shurui mono Oyogikata ga?—Nihon Eiho no Ichi ryuha ‘Suifu-ryu Suijutsu’ wo tazunete (Special Feature: Is Everyone Swimming? Why Are There 180 Different Swimming Strokes? — Exploring Suifu-ryu Suijutsu, a School of Japanese Traditional Swimming)” https://www.mizu.gr.jp/kikanshi/no77/07.html [in Japanese]

[1] Otai (sideways or sidestroke) is a swimming stroke in which the body lies on the surface of the water, like noshi-oyogi (squid-style swimming).

[2] Rittai is a standing swimming stroke in which the chin is always kept above the water surface.

[3] The Sengoku period refers to the period from the end of the 15th century to the end of the 16th century, when the shogunate lost its authority and wars broke out frequently.

[4] Among the more than 300 feudal domains that existed during the Edo period, the Tokugawa Gosanke were the three branches of the Tokugawa family that held a status second only to the Shogun family and were allowed to use the name Tokugawa. In other words, the “Tokugawa Gosanke” refers to the Owari Tokugawa family, the Kishu Tokugawa family, and the Mito Tokugawa family.

[5] Suifu was a Chinese-style alternative name for Mito during the Edo period, meaning the place where water gods or dragon kings reside in myths and legends.

Keywords

- Mizu no Bunka

- Mizkan Center for Water Culture

- Nihon eiho

- Japanese swimming techniques

- Suifu-Ryu

- Suifu school

- Suifu-ryu Suijutsu Association

- Arakawa Isami

- swimming

- martial art

- suijutsu

- combat swimming

- lifelong sport

- Mito City

- Naka River

- Lake Senba

- Tokugawa

- nagare to-oyogi

- long-distance swimming

- Naka River Long Distance Swimming Competition