Shogi and Artificial Intelligence

Advisor: SATO Yasumitsu, professional shogi player

KAMIYA Matake, Professor, National Defense Academy of Japan

The waves of the third artificial intelligence (AI) boom are now sweeping across Japan in the same way as earlier fads did in the 1950s and the 1980s. Referring to the ongoing craze in the country, leading Japanese economic magazine Shukan toyo keizai wrote in its 5 December 2015 issue, “not a single day passes by without hearing about AI.” Many companies in Japan are making AI-related announcements one after another. Seminars on AI are held in Tokyo almost every day.

But the question we must ask is this: Is the development of AI good news for mankind? From early on, many people in the world outside Japan forecast a dystopian future if AI were to surpass human intelligence. To cite an early example, Bill Joy, a U.S. computer scientist dubbed the Thomas Edison of the Internet, cautioned that robots with higher intelligence may compete with humans and threaten the latter’s survival when they become able to self-replicate in “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” an article he published in 2000. More recently, British theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking expressed the fear that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.” Speaking in concert, Microsoft founder Bill Gates also said, “I am in the camp that is concerned about the threat of super intelligence [to human beings].”

Behind their concern, there is the feeling of unease that humans will stop being the owners of the highest intelligence on earth. Humans cannot match many other animals in terms of physical abilities, such as power and speed. High intelligence is the very thing that has allowed humans to consider themselves as special beings distinguished from other animals. What will happen if and when AI surpasses human intelligence? Will humans really be able to continue their dominance as rulers of the earth in this situation? Won’t machines deprive humans of many intellectual jobs and dominate them, in effect?

Japanese Manga, Animations and AI

These arguments about the possible threats posed by AI have been small in number in Japan until recently, however. It has been said that Japanese manga comic books and animations have affected this tendency significantly with their depictions from early on of the bright future with active intellectual humanoids. For example, Tezuka Osamu (1928–1989), known as “the father of Japanese manga” and “the god of manga,” continued to draw Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), a manga in which the boy robot Atom with a heart like that of a human works and fights energetically for justice in the dream society of the twenty-first century, for many years from 1952. Tetsuwan Atomu was turned into an animation, and its humanoid protagonist became a hero among Japanese children in the period of high economic growth. (The animation was also broadcast overseas under the title Astro Boy.) Many AI and robot researchers and engineers working successfully in Japan today say that they chose their career due to the wish to make their dream of creating Atom come true. Tezuka set 7 April 2003 as Atom’s birthday. To commemorate this date, the Journal of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence ran a special feature on Atom in its issue dated March 2003. In another manga, Doraemon, which Fujiko F. Fujio (1933–1996) kept producing from 1970 until just before his death, a robot called Doraemon (also with a heart and feelings, just like humans) that travelled from the twenty-second century to the twentieth century lives with Nobita, an elementary school boy who is not good at studies, sports or just about everything else, and helps Nobita as his best friend. The animated version of Doraemon is still broadcast on television every week. The animation continues to fascinate many children, not only in Japan but also in other countries in East Asia.

Atom and Doraemon are new friends for humans that were created with the science and technology of the future. They never harm humans. They cooperate with humans and try to offer them service. In the meantime, humans do not discriminate against them, and treat them as their associates. This view of robots has symbolized the positive impressions of AI that the great majority of Japanese people have had.

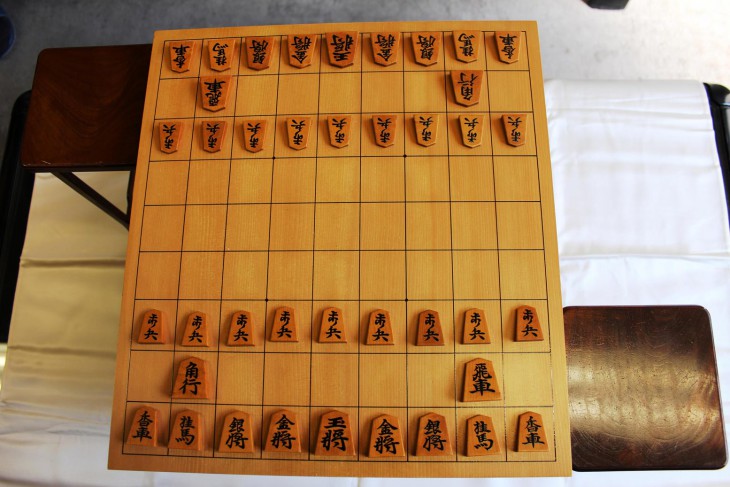

Shogi: A traditional shogi board with a set of shogi pieces in the starting setup. The stands on both sides of the board are used to hold captured pieces.

COURTESY OF JAPAN SHOGI ASSOCIATION

However, this situation has begun to change. The changes have been particularly noticeable since the spring of 2013. What limitless AI development will bring to humans has suddenly become an issue that is frequently discussed with a mixed sense of expectation and unease in Japanese society, too, in the midst of the AI boom described at the start of this article. What on earth was it that happened in Japan in the spring of 2013? What was it that caused the Japanese people’s attitude toward AI to change suddenly around that time?

It was neither a great scientist like Professor Hawking nor a prominent entrepreneur like Bill Gates. It was a board game native to Japan called shogi that caused this change. This must be an answer that puzzles most readers overseas. What is shogi in the first place? Why did it shake the Japanese people’s attitude toward AI? How can one board game have such a major influence on Japanese society?

Shogi is a Japanese version of chess. A board game called chaturanga that was played in ancient India spread to various parts of the world and branched out into games with original pieces and rules in the respective regions. Chaturanga changed into chess in the West, xiangqi in China and shogi in Japan. Shogi is a game that has been played widely among Japanese people, regardless of their class or financial standing, since around the sixteenth century when the current rules were established. Shogi remains popular today, with the playing population (the number of people who play shogi at least once each year) estimated at about 10 million among the total Japanese population of approximately 127 million.

The Den-osen Shock – Shogi as a Traditional Japanese Culture under Challenge

One historic series of shogi matches drew widespread public attention in Japan from March to April 2013. Five software programs that won in a shogi tournament for computer software in the previous year played against five professional shogi players in this series called Den-osen (Electronic King Championship). Against the odds, the software programs won overwhelmingly against the humans in these first serious shogi matches between humans and computer programs. The programs ended the series with a record of three wins, one loss and one draw. Major television stations, newspapers, magazines, Internet news sites and other media in Japan extensively reported the news that computer programs had beaten human professionals in the game of shogi. The news gave Japanese people a substantial shock. Following the historic shogi match series, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) televised a special program titled, “AI Outperforming Humans May be the Strongest in the World.” The human defeat in Den-osen made most Japanese people aware for the first time of the hard reality that, through continued development, AI was beginning to drag humans down from the leading role in intellectual activities that had been seen as revolving around them as a matter of course.

We suspect that even this explanation doesn’t make sense to many readers overseas. Shogi may be popular in Japan, but it’s only a game. Besides, in the world of chess, Deep Blue, a chess-playing computer developed by IBM, had defeated a human world champion sixteen years earlier, in 1997. Why on earth was the victory of computer programs over humans in the Japanese chess equivalent so significant after all those years?

To understand this point, readers overseas must understand that shogi is more than a game in Japan, and that it has been historically regarded as constituting part of traditional Japanese culture alongside the tea ceremony (sado) and Japanese flower arranging (ikebana). In the Edo period (1603–1867), the Tokugawa shogunate protected shogi and go, another traditional board game played in Japan. The shogunate paid the respective iemotos, or families heading game schools (three families for shogi and four families for go), a yearly allowance and urged them to compete against each other in terms of playing skills. Top shogi players centered on those from the three iemoto families were provided with an honorable opportunity to face each other across the board and demonstrate the results of their day-to-day studies in Edo Castle in the presence of the shogun every year in the lunar month of November. The shogun sometimes spoke to them directly on these occasions. (Top go players played matches in the presence of the shogun in the same way.)

There are countless parlor games around the world. From way back, many people have attempted to make a living by playing them. In the past, society usually viewed these people as gamblers. However, top shogi and go players in the Edo period were viewed differently. They were professionals who were officially recognized and salaried by the government of their time. Society showed them respect. From a global point of view, it was rare for such a system of professional game players to become established at this early a point. Its establishment shows that the Tokugawa shogunate considered shogi and go as cultures that it should develop.

Alongside go, shogi is widely recognized as a traditional Japanese culture in Japanese society today. People who have read Japanese newspapers must be aware that shogi and go columns appear in almost all of them every day. Speaking of shogi, there are currently approximately 200 professional players and about fifteen tournaments offering prizes in Japan. (In addition, there are several shogi tournaments open to female professionals only.) Parties such as newspapers, other media organizations, private companies and local governments sponsor almost all of these tournaments. With the exception of those that are televised, matches between professional shogi players usually take a whole day. In some cases, they continue for two days. One full year is spent on the majority of shogi tournaments for that reason. The respective newspapers cover the record of each shogi match in a self-sponsored tournament with an observer’s account written by an expert reporter over a period of several days.

Professional Shogi Players as Super Brains

The professional shogi players who win these tournaments, particularly the seven major ones, earn substantial prize money (42 million yen in the top-prize tournament). They are also treated as persons of distinction in Japanese society. For these reasons, many children and young people dream of becoming professional shogi players. The road to this career is extremely difficult to travel, though.

People who wish to become professional shogi players must “graduate” from the Shoreikai, an organization for training professional players operated by the Japan Shogi Association (Shoreikai means a society to encourage future players). Would-be professional shogi players usually join this organization in their elementary school days, or in junior high school at the latest. These hopefuls have the shogi-playing ability of the top amateur class at this point. They are children considered shogi geniuses in their respective local neighborhoods, because they have almost no rivals even among the elders. To obtain permission to join the Shoreikai, these hopefuls must achieve results above a certain level in matches against such strong peers and produce a score above a certain level in test matches against members of the Shoreikai. Accordingly, it is not easy to clear the first hurdle of joining the Shoreikai. About 70 to 100 would-be professionals undergo examinations to join the Shoreikai every year. Only about twenty of them pass.

Professional players SATO Yasumitsu (left) and HABU Yoshiharu compete in the final best-of-seven games series in one of the major professional shogi tournaments.

COURTESY OF JAPAN SHOGI ASSOCIATION

What is more, the Shoreikai is many times more difficult to graduate from than to join. The Shoreikai members play matches at ten levels, according to their ability. They are promoted or demoted according to the match results. New members are initially assigned to the second-lowest level. It takes them several years to more than a decade to reach the highest level from there. Only about one-fifth of hopefuls who join the Shoreikai survive and reach the top level. And then there is the final obstacle awaiting those who have managed to reach the highest level. Shoreikai members at this level play shogi in incomplete round-robin tournaments (each member who belongs to the top level plays eighteen games with different opponents preassigned at the start of the tournament) for six months twice each year. Only those members who finish this incomplete round robin in first and second places are allowed to become professional players. Those members who fail to become professionals before their 26th birthday must leave the Shoreikai, in principle. The Shoreikai had 160 members at the end of 2015, but only thirty of them belonged to the highest level. According to past statistics, only one half to two-thirds of them will become professionals. In other words, only about 10% to 15% of hopefuls who find their way into the Shoreikai are able to turn professional.

The intensity of the battles within the Shoreikai is well known in Japanese society. On 9 March 2014, Japanese newspapers reported in unison that Miyamoto Hiroshi, then 28, had gained his promotion to the rank of a professional shogi player by winning the final match in the Shoreikai’s top league. Why did the promotion of this obscure young man to the rank of professional become nationwide news? The fact is that the Shoreikai has an extra-time rule, which permits members who are over 26 years old to compete in the top league on the following occasion in cases where they post more wins than losses. Miyamoto had narrowly escaped membership withdrawal by posting more wins than losses in three consecutive incomplete round robin after surpassing the age limit of 26. In particular, in the incomplete round robin immediately before his promotion, which ran from April to September 2013, Miyamoto had a record of nine wins to eight losses at the point where he was about to go into the last match. He would be able to remain in the league if he won this last match and posted ten wins to eight losses. But by losing this match, he would also be forced to leave the Shoreikai. This is the situation that existed for Miyamoto. As a matter of fact, Miyamoto’s opponent in this crucial match was also 26 years old. This player came into the match with exactly the same record of nine wins to eight losses. In other words, this match was an unprecedented, eleventh-hour battle for both of these two hopefuls. Losing the match meant the end of the dream of becoming a professional for both of them. Miyamoto won the duel. He finally gained the qualifications to become a professional by finishing the following incomplete round robin, which was played from October 2013 to March 2014, in second place. The final match in this incomplete round robin was as ruthless as the last match in the previous one. Both Miyamoto and his opponent went into the match with twelve wins to five losses. They knew they would finish in second place if they won this last one. In other words, they were in a situation where only the winner could gain the status of a professional, which they had both chased for many years since childhood. Miyamoto won this decisive contest again.

Miyamoto, a contender who had survived by winning competitions against many boy wonders and girl wonders up to that point, made his dream come true at long last by enduring his battle with the age limit and winning the two life-or-death showdowns. Japanese people know what that means. Many TV programs and books produced in the past depicted the anguish of young people who failed to make it through the Shoreikai and become professionals, and have attracted considerable public attention. That is why the dramatic promotion of an unknown shogi player called Miyamoto became nationwide news in Japan.

People in Japan recognize about 200 shogi players who have overcome such competition within the Shoreikai and become professionals (only the top 0.00002% of approximately 10 million shogi players in Japan) as super brains, because the competition they undergo is so cruel. Computer software programs beat those supermen, though. The beaten professional shogi players included two top rankers who had won tournaments for professionals. The computer victories were no accident that occurred just once. In the second Den-osen series, played from February to April 2014, computer programs beat human professionals again with a record of four wins to one loss. Dwango Co., the Den-osen sponsor, broadcast all the matches in the second Den-osen series live on Niconico Douga, a leading video-sharing website in Japan under its operation. The number of people who watched at least one of those five matches on Niconico Douga totaled more than 2,130,000 in 2014. A large number of Japanese people, including those who are not shogi enthusiasts, witnessed how a computer software program could crush a human professional on a real-time basis and experienced a shock.

Rapid Development of Computer Shogi Software

To be sure, Japanese people knew that computers had grown stronger than humans in chess long before. However, Japanese people, particularly those who are enthusiastic about shogi, thought that computers would overtake humans in shogi only in the distant future, if they did so at all, because shogi is a game that is far more complex than chess. A shogi board has nine squares lengthwise and crosswise. It is larger than a chessboard, which has eight squares vertically and horizontally. Furthermore, forty pieces of eight types are used in shogi, compared with thirty-two pieces of six types employed in chess. And there is a rule peculiar to shogi that is not found in chess or other similar board games originating from chaturanga and played in countries around the world, including xiangqi. This rule allows players to use captured pieces. Shogi players keep the pieces taken from their opponent off-board as their reserve pieces. They can place such piece in a board position of their choice and start using the piece as their own when their turn to make a move comes. For this reason, a shogi match takes about 110 moves to finish on average, compared with the average number of chess moves of about 80 per match. Game-tree complexity (the number of possible games) for chess is 10123. The complexity for shogi is 10226.

The development of computer shogi programs ran into trouble because of this complexity. The development of the first computer system for playing shogi commenced in 1974. At the beginning, it was difficult to write a program that was able to finish a match without violating the rules. Many engineers began to publish a variety of computer shogi programs in the second half of the 1980s. Some of them were turned into products such as Famicom game software programs. However, the growth of their playing skills was slow compared with computer chess programs. Computer shogi programs were still weaker than the best human amateurs toward the end of the 1990s, when computers overtook humans in the world of chess. Observers were able to say with absolute certainty that computer programs had no chance of victory against professional shogi players. This situation continued.

| Game | Board Size | Number of Pieces | Number of Different Pieces | Game-Tree Complexity (Number of Possible Games) |

Average Game Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shogi | 9 x 9 | 40 | 8 | 10226 | 110 moves |

| Chess | 8 x 8 | 32 | 6 | 10123 | 80 moves |

It was around 2005 when this barrier was overcome and software programs that were able to beat professional shogi players from time to time finally appeared. Several years later, computer shogi programs achieved an evolution that was even more remarkable. At a press conference held after the completion of the fifth match in the 2014 Den-osen series, Tanigawa Koji, the president of the Japan Shogi Association who had won twenty-seven major tournaments (the fourth highest number in history), was forced to say, “I must admit that strong software programs today have more ability than middle-ranked professionals.” We can easily share the feelings of Tanigawa, who had to make such a remark as a top leader in shogi circles. However, even this statement might have been too sympathetic to humans. Without exception, computer shogi program researchers and developers have stated their views that are more pessimistic about humans. Professor Takizawa Takenobu of Waseda University, who serves as the president of the Computer Shogi Association, has the opinion that human shogi players are no longer competitors for computer software programs, with the exception of a handful of the strongest professionals. Answering my question, Takizawa hesitantly shared his forecast that shogi software programs would probably surpass the strongest human player in ability in two to three years. Professor Matsubara Hitoshi of Future University Hakodate, who acts as the president of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, takes a view that is even more merciless. Matsubara stresses the point that even the strongest human professional rarely finishes a shogi match without making a wrong move, but a computer program never makes a mistake even though it may have a bug. For that reason, Matsubara takes the view that humans have been driven into a corner where they no longer have any alternative but to look for a bug in order to compete with a software program.

Are Samurais on the Verge of Death?

Many professional players also take the view that computer shogi programs have started to threaten even top professionals. Kawaguchi Toshihiko, a professional player-turned-writer known for many books on shogi and respected among shogi enthusiasts as a storyteller who is able to share episodes from the world of professional shogi, told me the following in April 2014. (Kawaguchi passed away in January 2015). “I wonder . . . the four exceptionally strong players are likely the only human players today who are able to compete with computer (shogi) programs.” Kawaguchi stared at the display of a laptop computer in front of him with his head tilted to one side for a while after making the following statement: “I mean Habu Yoshiharu (who has won 94 major tournaments, the largest number in history), Watanabe Akira (who has won 17 such tournaments, the sixth largest number in history), Sato Yasumitsu (who has won 13 such tournaments, the seventh largest number in history, and Moriuchi Toshiyuki (who has won 12 such tournaments, the eighth largest number in history). Who else (can beat computer programs) aside from those four, I wonder?” The laptop display in front of us showed the fourth match in the Den-osen series played that year, in which a computer software program called Tsutsukana was beginning to crush Morishita Taku, a shogi player who had won eight professional tournaments and finished six major ones in second place. We were visiting Odawara Castle to watch this match. Odawara Castle is representative of Japanese castles built in the Edo period (1603–1867). It is located about a 30-minute Shinkansen (bullet train) ride from Tokyo. The venue for the match was set in this castle in a special arrangement for the occasion to bolster the image that shogi is a traditional Japanese culture. After following the match on the display for some time, Kawaguchi opened his mouth again and added quietly but with feeling, “They will become unable to beat the computer programs one of these days, but I hope they will delay the arrival of this time as much as they can.”

Katsumata Kiyokazu, a middle-ranked professional shogi player who had taken note of computer shogi programs since their early phase, has continued his studies and acts as a visiting professor at the University of Tokyo today, takes an even harsher view. At Odawara Castle, Katsumata said to me in a matter-of-fact tone, “I think that computer programs have practically surpassed humans.” In reply to my question as to what he meant by the word “practically,” Katsumata confidently said, “I can no longer beat computer programs. But I think that Habu, the strongest human player, could beat all the programs if he did something like taking leave from all matches for one year and studying specific software programs. I think Sato, who is here today, could also beat the programs if he did something like that. (Sato Yasumitsu brought the author to this venue, which was off-limits to people who had nothing to do with the match.) But I don’t think they can do things like that.”

MORISHITA Taku competes in the fourth match in the 2014 Den-osen series against the computer software program Tsutsukana. COURTESY OF JAPAN SHOGI ASSOCIATION

The Niconico Douga video-sharing site circulated the following message at the beginning of the live webcast of the fifth Den-osen match played one week later.

The world until yesterday and the world from today

What has changed and what has remained unchanged?

[Omission here]

What we are watching is a show that forces the samurais who survive in this modern age to face the latest weapons and die a noble death in the battlefield in a manner befitting warriors (meaning graciously and beautifully).

In this match, a computer software program called Ponanza beat Yashiki Nobuyuki, a strong professional shogi player ranked tenth who had three career major tournament victories at that point. Access counts for the Niconico Douga live webcast of the match surpassed 630,000. The news that human players had won only two of ten matches played against computer programs in the past two years (with one draw) flew about in the mass media after Yashiki’s defeat. Computers have demonstrated their amazing ability in an area of traditional Japanese culture. They are beginning to overwhelm flesh-and-blood super intellectuals. Readers who have read this far in this article should now understand how great this shock was to Japanese people. In this way, shogi became a cause for Japanese people to feel uneasy about the possibility that AI may force humans out of their position as the beings with the highest intelligence on earth with its continued evolution, in the same way that Joy and Hawking did.

Will There Be a Human Counteroffensive?

Will machines called computers deprive professionals called shogi players of the reason for their existence in the not-too-distant future? Surprisingly, few people, including professional players, computer shogi program researchers and their developers, appear to think that way yet, at least at this point.

To begin with, many professional shogi players think that humans lose to computer programs because they make mistakes. They believe that humans can compete with software programs sufficiently in terms of their ability to make predictions. For example, Sato Yasumitsu said he received the impression that computer programs beat human professionals in the Den-osen series of matches by taking advantage of human weaknesses. In other words, professional shogi players lost many matches against computer programs by making thoughtless mistakes after developing a favorable position for a period. Computers win matches against humans because humans make mistakes. Looking at it from the opposing direction, Sato suggests that humans would shape their positions better than computer programs if there were no mistakes.

From this point of view, Morishita Taku, a professional player who had lost to Tsutsukana at Odawara Castle, raised an issue and pointed out the need for special rules for matches between humans and computer programs. Looking back on the lost match with a positive attitude, Morishita said, “It was an extremely good opportunity for me, and it reignited my passion for shogi after a long time. It was wonderfully productive.” At the same time, however, Morishita asserted that it was not fair to apply exactly the same rules for human-to-human matches to clashes between humans who unavoidably make errors and computer programs that make no mistakes whatsoever. A player loses everything in a shogi match by making a single mistake after ninety-nine great moves. Accordingly, special rules that minimize the chances of human error are necessary for determining whether humans or computer programs have shogi-playing skills that are purely higher in level. That was Morishita’s opinion. His specific proposal was to supply human players with a shogi board and a complete set of pieces separately from those used in the match for studying moves, and to sufficiently extend the time limit for considering the next move. Explaining that he made almost no mistakes in practice matches using the separate board and pieces under a rule of 15 minutes allowed per move, Morishita stated confidently that strong professional players would be able to beat computer shogi programs under those conditions.

Nine months later, Morishita proved in person that there were grounds for his confidence. Morishita was granted an opportunity to face Tsutsukana, the program that had beaten him nine months earlier (its updated version, to be precise), again from December 31, 2014 to January 1, 2015 under the rules he had proposed, with the exception of a slightly shorter time limit of ten minutes per move. The Niconico Douga site webcast this match live again. The match was suspended about twenty hours after it started in consideration for human fatigue, because the extended time limit caused it to run for too long. Morishita stunned the people who were watching the match on the Net by not making any thoughtless moves. Morishita dominated Tsutsukana on the board from early on. He gradually solidified his dominance to the point of building a position that made his victory almost certain at the point of the match suspension.

Not all professional shogi players support Morishita’s proposal of allowing humans to use a separate board and pieces for considering moves, however. “I think that shogi was originally designed to be played in the head only,” said Sato. “I grew up listening to my teachers, who said that we cannot improve our playing skills by thinking about how to move pieces by actually moving them on the board. That’s not training, they said. Accordingly, I am resistant to the idea of considering moves using a separate board and pieces.”

Many professional shogi players appear to feel the same way as Sato. The Japan Shogi Association has not adopted the rules proposed by Morishita in subsequent matches between humans and computer programs. However, there is no doubt that Morishita proved with his own ability the correctness of his theory that humans are not inferior to computer programs when human error is eliminated.

In the meantime, another group of professional shogi players emerged. They focus on the point that computer programs are error-free, but that they have bugs. In the Den-osen Final series played from March to April 2015, two professional shogi players beat software programs by taking aim at their bugs. On the team level, humans beat computer programs for the first time, too, posting three wins to two losses. In the Den-osen series, computer software updates are prohibited about three months before each match. The latest versions of the software programs at that point are supplied to humans for advance studies. These studies enabled professional shogi players to discover any bugs before the 2015 Den-osen series.

There is criticism that this approach to playing shogi goes against the essence of the board game. To cite an example, the Nihon keizai shimbun newspaper wrote, “It is difficult to align the aesthetic sense that professionals are those who fascinate viewers with the gambler-like attitude of thinking only about victories.” Sato also said, “I don’t want to do things like searching for bugs.” However, Katsumata is positive. Katsumata said, “We began to get to know the habits and weaknesses of computer software programs thanks to the experience we accumulated through the last three series of matches against them.” The Sankei shimbun newspaper called the attitude of professional players who “dared to make bad moves outside tesuji (sequence of the best moves) and invited computer programs to function irregularly” by “studying their habits and blind spots exhaustively” a “type of tenacious guerrilla tactics.”

Takizawa, who has spent more than forty years developing a shogi software program that is able to beat humans, said that the Den-osen Final was a series of “matches typical of those played between humans and computer programs.” Takizawa provided the following explanation: “Professional shogi players thoroughly studied computer programs’ playing logic and attacked their weaknesses. They showed that humans can beat computer programs depending on how they play, although they are no match for the programs in terms of simple prediction depth.” Takizawa then said, “Matches against humans will remain extremely meaningful, because computer programs can work out countermoves when weaknesses are found in this way.”

Takizawa’s words express the heartfelt respect he feels for the strength displayed by professional shogi players. Shogi professionals have splendid abilities and skills. Their losses to computer software programs do not tarnish their value. I talked to numerous computer shogi researchers and developers to prepare myself for this contribution. Many of those people told me the same thing. For example, Takeuchi Akira, the developer of Shueso, a computer shogi program that beat one of the professional players and won the title of MVP in the 2014 Den-osen series, replied promptly as follows when I asked him when computer programs would surpass humans: “I don’t think computer programs have surpassed humans even at the point where they begin to beat professional shogi players.” Takeuchi said that he finds that there is a lack of sensibility in shogi played by computer programs compared to shogi played by humans. For example, professional shogi players seek a victory, but, at the same time, they want to make their victory the outcome of beautiful shogi or a well-played game, if doing so is at all possible. “Machines do not have such sensibility,” pointed out Takeuchi. “My goal has been and will always be to develop a software program that achieves this style of shogi.” Takeuchi added that professional shogi players might be able to discover “depth not previously found in shogi” by joining forces with computer programs.

In the meantime, professional shogi players pay candid respect to the evolution of computer shogi programs and also acknowledge their strength. For example, Toyama Yusuke, a professional player who has been overseeing the Japan Shogi Association’s mobile business as its mobile chief editor, said that professional players were able to win the 2015 Den-osen matches because they “had recognized the strength of software programs and made mental preparations to deal with it.” Sato said that computer programs had begun playing “impressive shogi” in recent years. He said that he had had absolutely no interest in playing shogi against the programs before, but that he had recently started to think that competition with the programs that play shogi so well might help him to improve his shogi skills and find the best move in each position.

Sato also said the following to me on our way back from Odawara Castle, where we witnessed Morishita’s Den-osen loss to Tsutsukana. “Tsutsukana played shogi impressively well today. But looking at the order of the moves it made, I felt that Tsutsukana played the game in a very narrow way.” Unable to understand exactly what he meant, I asked him what the narrow way of playing shogi was. In reply, Sato said, “It’s hard to explain, but the way Tsutsukana played was a risky way of playing shogi, which has only one correct path outside of which everything else fails.” In spite of this, computer programs are winning. Isn’t it OK for the programs to play shogi in whatever way they choose as long as the chosen way leads to victories? In response to this second question, Sato said, “Well, it’s the course, it’s a way of playing that humans never choose.” I did not understand what Sato truly meant by those words at that point.

What Is the Best Move in the True Sense of the Word? – Is It Possible for Humans to Live Symbiotically with Computers?

Several months later, I had dinner with Sato one evening. After our dinner, I drove him to his house. The car navigation system in my car instructed me to make a right at the next intersection when we reached a neighborhood close to his house. But Sato told me to go straight ahead, instead of turning right there, because that was the correct route. The car navigation system repeated the instruction to turn right as we moved closer to the following two intersections. Sato kept telling me to drive straight ahead, though. “Sato-sensei, what on earth will happen if I make rights?” In response to my question, Sato said, “We can certainly reach my house by turning right at those crossroads. It may even be a quicker route. But the roads on the way are winding or narrow, and are difficult to travel down. It’s a route that we want to avoid under normal conditions. Machines seem to have no consideration for such things.”

At that point, what Sato had said to me in Odawara flashed back into my head out of the blue. “Sensei, you told me in Odawara that computer programs play shogi in a narrow way,” I said to him to seek his confirmation. “Do you remember that? Did you mean something like this? We will certainly reach your house by following what the car navigation system tells us. We will reach it more quickly that way than by driving straight ahead. But that would be a choice that is too risky for humans to take in view of the possibility of human error. When seeking victories in shogi, computer programs nonchalantly make choices with great risks that humans would not make. They do so because machines make no human error. Humans don’t imitate such choices. They should not do so. Sensei, is my understanding correct?”

Sato remained silent for a while. He seemed to be giving some thought to the point I had just raised. He then said, “You may be right.” Continuing, Sato said, “I think the point is what is best in the true sense of the word. I have always thought that finding the best move is the job of shogi professionals. I think discovering that is different from just finding a way to win matches. I think it will be interesting if professional shogi players join forces with computer programs in the future to discover what is best.”

Humans may become able to unravel truths and the best moves in shogi, which have been invisible, by competing and joining forces with computer programs. A wide spectrum of professional shogi players and the researchers and developers of computer shogi programs share this way of thinking that Takeuchi and Sato have mentioned. Many of them appear to think that humans and computers can live symbiotically by respecting each other and taking advantage of each other’s strong points. It will be impossible to arrest the development of AI in the future world. The author thought that the attitude of seeking symbiotic coexistence would be essential for preventing a course toward a future where humans are not needed.

The Japan Shogi Association completed the Den-osen series of five matches between humans and computer programs with the Den-osen Final series in 2015, and launched a new Den-osen series in which the winners of separate tournaments for professional players and computer programs play a championship match. Shogi is likely to continue attracting keen interest in Japan as a test ground for human-AI coexistence.

Translated from an original article in Japanese written for Discuss Japan. [March 2016]

Note: This article was written by the author with the cooperation of the professional Shogi player Sato Yasumitsu and the Japan Shogi Association.