The Splendor of Wagashi Culture: Features of Jogashi Dating Back to the 17th Century

Jonamagashi made by Toraya. Clockwise from right, yakoeman (rooster’s crow bun), yamaji no nishiki (mountain path brocade), shimokobai (frosty red plum blossom), senkanotomo (friend of hermit’s place), and (center) egaoman (smiling bun).

Photo: Yasumuro Hisamitsu / Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko)

Nakayama Keiko, Senior Researcher of Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko)

Jonamagashi (Japanese-style fresh confectionery strongly associated with the tea ceremony), with their literary confectionery names such as “harugasumi” (spring haze) and “hatsumomiji” (first red autumn leaves) expressing the natural features of the season, are unique to Japan They are thought to have originated in jogashi (high –grade confectionery) which spread mostly in Kyoto in the latter half of the 17th century. Let’s look at the background of its development and the characteristics of this Japanese confection.

Luxurious Sweets Made Using White Sugar

Sugar, the main ingredient in sweets, was for a long time an expensive and rare item that needed to be imported since first brought from China in the Nara period (710–794). The situation didn’t change much during the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1603) when Sen no Rikyu (1522–1591) established wabi-cha (Japanese tea ceremony). The kashi (confectionery)[1] seen in the Matsuya kaiki (a record of tea ceremonies from 1533–1650), the Rikyu hyakukai ki (a record of Rikyu’s one hundred tea ceremonies from 1590–1591), and other records of tea ceremonies include rice cakes and rice crackers, chestnuts and persimmons, kelp, and nishime (boiled and seasoned root vegetable) and did not include the sweet foods of today. However, after a time of warring ended and upon entering the Edo period (1603–1867), society stabilized, the commodity economy developed, and the amount of imported sugar increased through trade with the Netherlands and China. Time to enjoy food emerged, and a variety of sweets came to be made as sweet luxury items. Of particular interest is jogashi, which spread mostly in Kyoto during the latter half of the 17th century, a vibrant period of time when Genroku culture[2] flourished. Different from the inexpensive mochi (rice cake) sweets and dumplings sold at temple and shrine gates, amusement districts, and in tea shops along main roads, jogashi were luxury items made using white sugar which was top quality at the time. Shops selling these sweets were known as “jogashi-ya” (jogashi shops) and their customers included the imperial court, court nobles, influential samurai families, temples and shrines, and upper class townspeople.

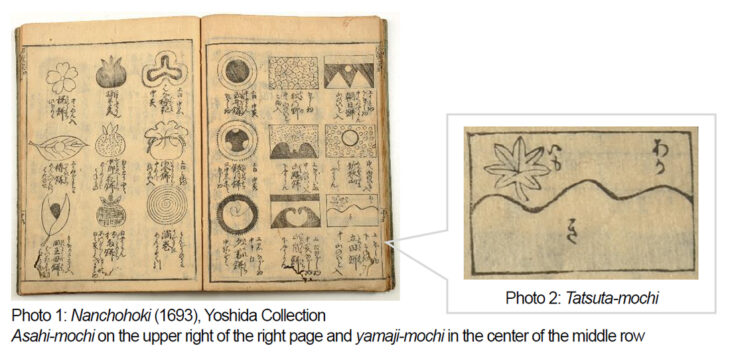

One of the main features of jogashi is that many of the literary confectionery names and designs are related to seasonal natural features. The nearly 100 varieties of confectionery names found in the Kikyoya kashi mokuroku (Kikyoya confectionery catalog) from 1683 (recorded in Ichiwa ichigen [One tale, one saying] by Ota Nanpo [1749–1823]) provide useful information on the confectionery’s development and spread. Confectionery names include “usuyuki mochi” (usuyuki [light snowfall]), “ominaeshi mochi” (ominaeshi [eastern valerian] appears in the oldest waka anthology, the Man’yoshu, as one of the seven autumn flowers written about by the poet Yamanoue no Okura [660?–733?]) and “fujibakama” (eupatorium perfoliatum) is a chapter title in The Tale of Genji)[3]. Kikyoya, which produced the catalog, was a “kudari kyogashiya” (confectionery shop from the Kyoto captial) with a shop in Nihonbashi in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and is thought to have been associated with Kikyoya, purveyor to the Imperial Court in Kyoto. However, as there are no illustrations in the catalog, it is unclear in what shapes the sweets were made. The oldest designs are listed in the Nanchohoki (Handbook for men) from 1693, and in the fourth volume, we can see 24 illustrations and about 250 confectionery names. This book is representative of the many chohoki (handbooks) published during the Genroku period, and it is consider to be an encyclopedic practical book listing etiquette and knowledge that men should learn. As chanoyu (tea ceremony) spread, confectionery illustrations were also included as something well-educated men should be well versed about.

The designs call to mind the jonamagashi of today (photo 1). Some of the ingredients are listed along with the confectionery names and we can imagine roughly the production method. We know the square illustration on the right is a cross section of the yokan-like saogashi (Japanese sweets in the form of long blocks), as neri-yokan (yokan made of boiled and mashed adzuki beans solidified with agar) did not yet exist in this period. It is thought that it was made of a dough similar to mushi-yokan (steamed adzuki-bean paste containing flour) and uiro (sweet rice jelly). Some of the designs are pictorial, such as asahi-mochi (mochi designed like the rising sun over the mountains) and yamaji-mochi (mochi designed in a way reminiscent of a mountain path) where the shape of the sun and flowers is imitated by yamaimo (Japanese yam). Tatsuta-mochi (photo 2) is associated with Tatsuta (or the Tatsutagawa River), a place in present-day Nara Prefecture which is famous for its autumn leaves. The upper part of the dough is red, the lower part yellow, and the maple leaf design is white and made from yamaimo. The color red was made with safflower and yellow with seeds of the gardenia, and the sweet likely represented the beauty of autumn leaves. Also on the left are chakin shibori (confections where the shape is formed by a squeezing motion using a cloth) and sweets made into the shape of a cherry blossom and peach. It is surprising that confectionery names and designs as seen today were already invented more than 300 years ago.

Illustrated Wagashi Books Acting as Product Catalogs

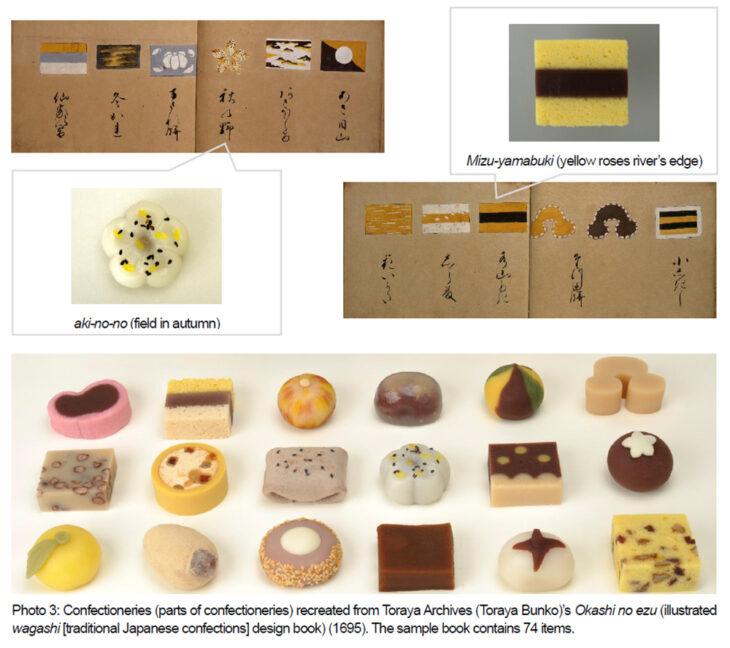

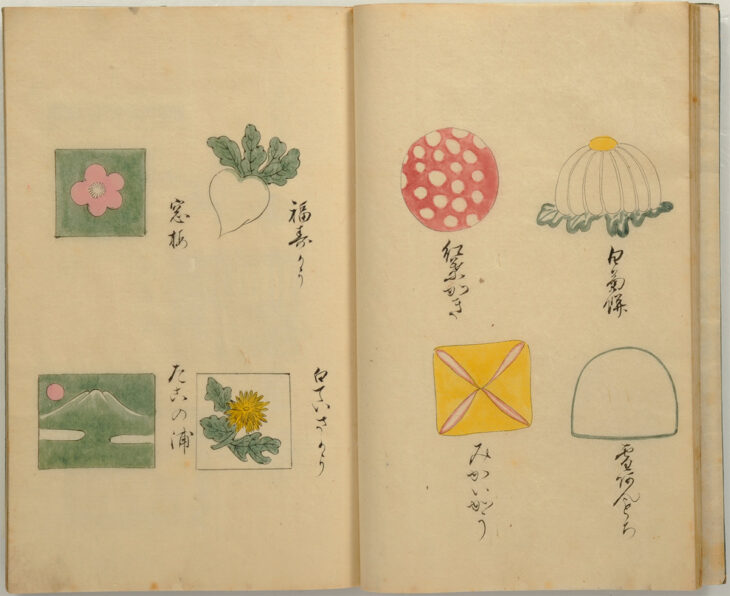

The illustrations in the aforementioned Nanchohoki are thought to have been based on the colorful kashimihon-cho (illustrated wagashi [traditional Japanese confections] books) of jogashi-ya. These illustrated wagashi books, also called ezu-cho or hinagata, were used as product catalogs, but only a limited number were produced as they were hand-written at the time. The oldest existing illustrated wagashi book is one by Toraya from 1695. Some of the sweets listed are still produced and can be seen in shops today (photo 3).

Confectionery sample books from the Edo period still exist today, including some by Kikyoya and Futakuchiya, which like Toraya were Kyoto’s purveyors to the Imperial Court, but they rarely note when they were written. Though there are some differences in style and in the way the sample books were drawn, many of the confectionery names and designs were similar, and we can assume that many jogashi-ya produced similar confectioneries as there were no registered trademarks at that time. In the section about rakugan (dry confectionery) from the Gorui nichiyo ryouri sho (Assorted daily cooking recipes extracts) published in 1689, we find this passage. “Use a spatula to pack the prepared sugar and domyoji-ko (coarse rice powder) mixture into the wooden molds engraved with various motifs such as chrysanthemums, fans, flowers, and living things. Hit the wooden mold downward, and the rakugan is completed.” This reveals that people were using wooden molds carved with plant, animal, and daily item designs in the latter half of the 17th century. Wooden molds are expendable objects, few are marked with dates, and few original models exist today, but the fact that a variety of rakugan designs were created is very interesting (photo 4). Rakugan and other higashi (generic name for dry confectioneries), which are made with white sugar, are also considered jogashi and were prized for how long they would keep and for the beauty of their designs.

Photo 4: Wooden mold for confectionery, “Yatsuhashi” (1709), Collection of Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko)

It is the oldest among the dated wooden molds owned by Toraya. Like Ogata Korin (1658-1716)’s “Kakitsubata-zu” (Irises), the design is related to Ise Monogatari (The Tales of Ise).

Confectionery Names and Designs

We can categorize jogashi motifs as follows based on the Nanchohoki, Toraya’s illustrated wagashi books, and more.

- Plants: ume (plum), sakura (cherry blossom), kiku (chrysanthemum), kakitsubata (iris), botan (peony), kikyo (bellflower), kaede (maple)

- Animals: chidori (plover), kari (wild goose), uzura (quail), kujira (whale)

- Natural phenomena: ame (rain), yuki (snow), kasumi (haze), kumo (clouds)

- Scenery: asahi (sunrise), tsuki (moon), yama (mountains), kawa (rivers), famous places such as Tatsuta (Nara Prefecture) and Sagano (Kyoto Prefecture)

- Daily items, etc.: ogi (fans), chakin-bukuro (bag made from cloth for tea ceremony), tanzaku (strips of paper)

These are all familiar to Japanese people through waka poetry and art. For each, elegant words seen in classical literature, including cultural works such as the Kokin wakashu and the Tale of Genji, were given as confectionery names. Tatsuta-mochi and tatsutagawa were associated with “Tatsutagawa momiji midarete nagarumeri wataraba nishiki nakaya taenan” (“The autumn leaves are flowing scattered in Tatsutagawa River. If I crossed the river, would the brocade of the leaves be cut off halfway through?”), translation from Kaleidoscope of Books, https://www.ndl.go.jp/kaleido/) (Kokin Wakashu, Vol. 5. Seasons: Autumn 2, author unknown), and for wakamurasaki, one would think of characters from The Tale of Genji. Someone would have tasted the sweet with an intellectual playfulness by relating it to the world of classical literature.

The fun of expanding one’s imagination from these confectionery names and designs could be said to have developed from the tea ceremony. Special tea utensils were used regularly since the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490), the 8th shogun of the Muromachi Shogunate when Higashiyama culture flourished, and the names given to these utensils became respected more and more. Daimyo (feudal load) tea master Kobori Enshu (1579–1647) from the early Edo period in particular recalled the world of waka poems with his so-called keshiki (landscapes)[4]. He gave them names associated with waka poems, including “asukagawa” (Asuka River in Nara Prefecture, for example, is the river that appears most frequently in waka poems written in the Manyoshu [about 4,500 poems]) and “murasame” (meaning passing shower particularly in the poetic tradition), which also influenced later tea masters. It was surely natural to want to incorporate the same idea with confectionery names.

We can broadly divide jogashi designs into two categories: concrete and abstract. You can easily tell what the concrete designs represent from looking at them, be it the shape of a cherry blossom or the moon. It is thought that confectioners often drew inspiration from works of art when creating these designs. In the kimono model books, akin to fashion books, that were already being published in the Kanbun era (1661–73), we can see many designs based on the world of classical literary arts such as stories, tales, and poetry. Confectioners probably used these designs as reference or took parts of patterns and applied them to sweets. It is also thought that the works of the Rinpa school, represented by Ogata Korin (1658–1716)[5] and Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743) who followed in the footsteps of artist and tea master Hon’ami Koetsu (1558–1637) and furniture designer and painter Tawaraya Sotatsu (1570–1640), were inspired by the elegant dynastic world while inspiring the vitality of townspeople culture, and their innovative, refined designs became models for confectionery making.

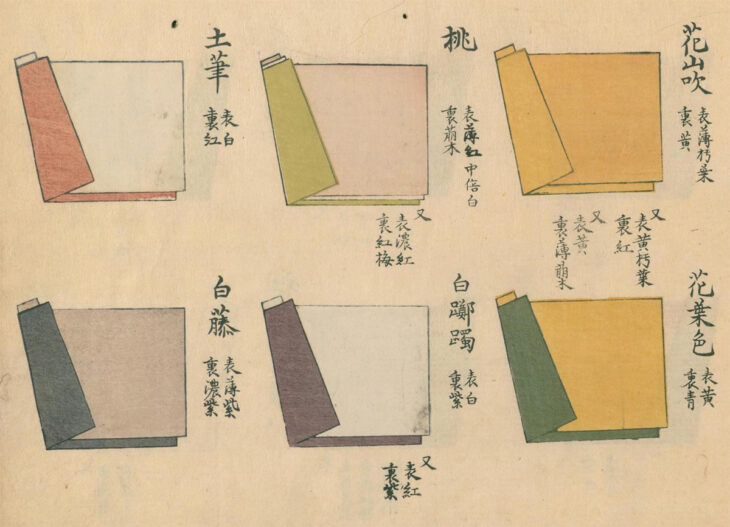

On the other hand, it is not possible to understand abstract designs at first glance. They require creativity and a playful mind to imagine what they represent based on the confectionery’s name. Colors are especially important, with ki (yellow) depicting yamabuki (Japanese kerria), ominaeshi (eastern valerian), and kiku (chrysanthemum); usubeni (light pink) depicting plums and cherry blossoms; aka (red) depicting autumn leaves, shiro (white) depicting snow, and murasaki (purple) depicting wisteria flowers. This choice of color gives the impression of the kasane no irome (layer color combination) of the clothing of Heian period aristocrats (photo 5). During this period, aristocrats wore many pieces of clothing in a layered style, later called “junihitoe” (literally twelve layers, the formal court dress for women worn at ceremonies and on other important occasions). The color gradations created by the layering of clothing, and the color schemes of the front and back of the clothing evoked images of seasonal plants and were given names such as “yamabuki-gasane” (kerria layer) and “ume-gasane” (plum layer). The detailed aesthetic seen in the color schemes of this clothing is still alive in the jogashi of the Edo period. In the late Edo period, confectionery names such as “matsugasane” (pine layer) and “momijigasane” (autumn leaves layer) appeared, reflecting the fact that confectioners consciously incorporated this aesthetic into their sweets. This is true of colors and ingredients, as well. A slice of yokan containing whole adzuki beans would express cherry blossom petals, autumn leaves, and plovers (a type of bird), and confectionery names would be given, such as “sakuragawa” (Sakura River), “hana-momiji” (cherry blossoms and autumn leaves), and “hama-chidori” (plovers on the beach). The aesthetic of appearances can be seen in various aspects of Japanese culture, including gardens resembling the pure land world and scenic spots, and kabuki shows and colored prints based on the classics, and the world of confectioneries is no exception.

Photo 5: “Kasane no irome” (layer color combination), Collection of the National Diet Library

The colors of the front and back of the clothing also corresponded to the four seasons

The Refinement and Spread of Jogashi

Jogashi were developed and refined by the educated upper class and people of culture. The relationship between confectionery and customer at the time was much closer than it is today, and we can say that there was frequent communication regarding the creation of confectionery names and designs. The fact that sweets are used as gifts for events, ceremonies, weddings, and funerals, and for tea ceremonies, may also have contributed to their development. For Toraya, they had orders not just from the imperial court and court nobles, but also from samurai families, sending sweets to daimyo staying in Otsu or Osaka near Kyoto or as gifts for daimyo from court nobles and temples. When alternating their stays between Edo or Kyoto, the daimyo surely had many chances to see and taste beautiful jogashi. In some cases, a daimyo with deep knowledge of the tea ceremony would have his confectionery purveyor learn techniques or bring in highly regarded confectioneries, and jogashi gradually spread to castle towns across Japan.

Regarding the use of sweets in tea ceremonies, in the Senke branch of wabi-cha that originated with Sen no Rikyu, there is a tendency to place emphasis on sweets made by tea ceremony masters, and it is thought that jogashi was used in the daimyo tea system, which was derived from daimyo tea masters Furuta Oribe (1544–1615) and Kobori Enshu, as well as in extravagant tea parties for the wealthy. For example, many of the sweets seen on the menu for cha-kaiseki (the light meal served in the tea ceremony) in the Chanoyu kondate shinan (Tea ceremony menu guide) written by Endo Genkan (birth and death dates unknown, around the Genroku period), a tea master of the Kobori Enshu school, are thought to be jogashi.

In the eighteenth century, the amount of jogashi being made increased due to the promotion of domestic production of sugar by the 8th Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune, and in addition to improvements in production techniques, jogashi evolved further, with attractive and elaborate skills developed. At the height of the late Edo period in the first half of the 19th century, we can see that a wide variety of beautiful sweets were being made from an illustrated wagashi book (photo 6) of Kanazawa Tango, confectionery purveyor to the Edo Shogunate, and an e-dehon (illustrated wagashi book) of Sohonke Surugaya (originator of Suruga-ya), confectionery purveyor to the Kishu Tokugawa family in Kishu Domain (Wakayama and southern Mie Prefectures). As we reach the Meiji period, the terms “confectionery purveyor” and “jogashi-ya” gradually died out, but the jogashi tradition was passed on and continues today.

Photo 6: Kashi-fu (confectionery records), Collection of Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko)

An illustrated wagashi book of Kanazawa Tango in Edo, which served as a purveyor to the Edo Shogunate.

One phrase describing the charm of wagashi states that “wagashi is the art of the five senses.”[6] There is the beauty of its appearance, a delicious taste, the physical sensations of cutting with a wagashi pick and the elasticity and softness when feeling with the mouth, the subtle aroma of the plant materials, and finally, hearing the confectionery names and expanding one’s imagination. The fact that these sweets, which evoke the five senses in this way, were developed in the latter half of the 17th century based on an ancient Japanese aesthetic and continue to be produced today shows the power and depth of the traditions of wagashi culture. It is hoped that the charm of wagashi, a rare presence among the confectionery cultures of the world, will be passed on to the future.

References:

“Chanoyu no mei daihyakka (Encyclopedia of names in the tea ceremony),” supervised by Arima Raitei, Inahata Teiko and Tsutsui Hiroichi, Tankosha, 2005

“Tokushu: Kinsei kashi mihoncho (Special Feature: Illustrated wagashi books of the Edo period),” Wagashi, No. 27, Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko), 2020

Nakayama Keiko,“Genroku-ki to wagashi isho (Genroku period and Japanese confectionery design),” Wagashi, No. 3, Toraya Archives (Toraya Bunko), 1996

Nakayama Keiko, “Genroku-ki no kashi to Toraya shiryo (Genroku Era Confectionery and Toraya Archives),” Kaiseki to kashi (Kaiseki and Confectionery), System of Tea Ceremony 4, Tankosha, 1999

Translated from “Wagashi no Rekishi III-1, 17 seiki ni sakanoboru jogashi no tokucho (The History of Wagashi III-1, The Splendor of Wagashi Culture: Features of Jogashi Dating Back to the 17th Century),” vesta No. 128 2022 Autumn, pp. 20–25. (Courtesy of Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture) [March 2023]

Keywords

- Nakayama Keiko

- Toraya Archives

- Toraya Bunko

- wagashi

- jonamagashi

- jogashi

- confectionery

- classical literature

- tea ceremony

- white sugar

- Genroku culture

- Kikyoya

- Futakuchiya

- Nanchohoki

- confectionery sample books

- wooden molds

- rakugan

- The Tale of Genji

- Man’yoshu

- Kokin wakashu

- Heian period

- seasonal plants

- gardens