How Management Can Make the Most of Diverse Human Resources – Increasing Women’s Participation Will Change Corporate Management and the Japanese Economy

How to take advantage of women’s abilities is an important issue for both the Japanese economy in general and corporations in particular. This feature story will examine why it is important to utilize women’s power, what kind of positive effects the full employment of women will bring about economically, and how the employment of women should be promoted.

KOMINE Takao, Professor of Hosei University

The employment of women in Japan lags behind international standards

What is the current situation regarding women’s participation in Japanese society? Let’s make an international comparison regarding women’s participation from two perspectives, their involvement in social decisions and their participation through employment.

First, regarding the extent of women’s participation in social decisions, the World Economic Forum publishes the Global Gender Gap Index. This index tracks women’s employment status, level of educational attainment and health, participation in politics, and other factors. In the Global Gender Gap Report 2012, the latest report, of 135 countries, Japan was ranked at 101, more or less the lowest among developed economies (except for South Korea, which was ranked at 108).

Second, let’s look at women’s participation in the labor market. The rate that comprehensively indicates the extent to which men and women participate in the labor market is the total wages of men and women. The gap in total wages comprehensively shows the gap between men and women in number of employees, working hours, and wages per hour.

I participated in a survey, How Women Will Change the Economy and Finance, conducted by the Japan Center for Economic Research, for which I served as advisor. This survey was designed to send the message that women could change the Japanese economy in the future, and the key to revitalizing the Japanese economy is to make the most of women’s abilities.

Although the data is slightly out of date, as of 2005, when the project was carried out, the total wages paid to women in Japan were only 38.2% of those paid to men, making Japan the lowest ranked among the developed economies surveyed (the figure for Norway, for example, was 73.7%). Three complex factors are attributable to these results in Japan. They are: (i) the relatively low percentage of female employees; (ii) the shorter working hours for women; and (iii) the large gap in hourly wages between men and women. The factor that had a particularly significant impact was (iii), the large gap in wages.

Assuming that GDP is maintained at the same ratio between men and women, if Japanese women participated in the labor market to the same extent as they do in Norway, Japan’s GDP and income per capita could be estimated to increase by as much as 23% above current figures. This is a rough estimation that assumes that an increase in the female workforce would directly result in an increase in income for the overall economy. However, even this estimate shows how much women can potentially contribute to growth.

Demographic onus and the utilization of women

Next, let’s look at the fact that the utilization of women has become important, particularly in Japan, from the perspective of addressing the population problems.

As Japan is experiencing a rapidly aging population and a declining birthrate, it is my view that the heart of our population problem is the demographic onus (a phenomenon in which the percentage of the working population of the overall population declines).

Japan’s birthrate and population are declining. If this declining birthrate continues, the base of the demographic pyramid will become narrower, and this demographic group, which makes up a large proportion, will gradually move up.

If the largest demographic group is the working age population (15–64 years old), the proportion of working people in the overall economy will increase (or the labor participation rate will rise). In short, as the relative proportion of the people who work and earn grows, economic growth is facilitated. This stage is called the “demographic dividend.” Japan experienced its high-growth era during this demographic dividend.

However, after a while, this broad population group will start to move to the senior population group (people aged 65 or above). When that happens, contrary to the period of the demographic dividend, the proportion of the working population shrinks, adversely affecting the economy. This is the demographic onus (implying burden).

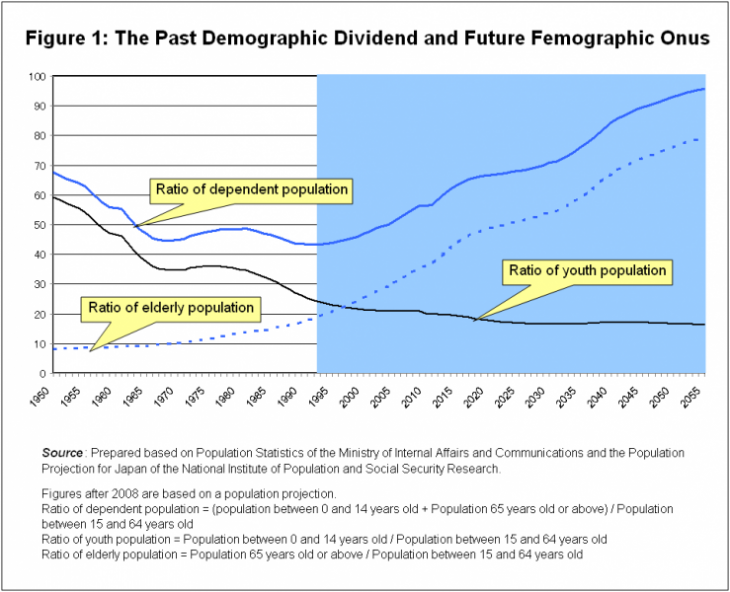

Figure 1 shows the trends in the ratio of the dependent population. This ratio is calculated by dividing the total youth population and elderly population by the working-age population. If the working-age population consists of working people, a higher dependent population percentage means that the population is heading for a demographic onus. The figure shows that Japan has been in a demographic onus period since the 1990s, and the level of this onus has been rising steadily. Once the period of a demographic onus sets in, a labor shortage takes place and the number of people who can save declines. As a result, economic growth stagnates, and the social security system, which is a pay-as-you-go system, comes to a standstill, while the regional economy, which the working-age population flows out of, becomes exhausted.

Now, raising the overall labor force participation rate in Japan is an effective way to counter this population onus. As explained above, the labor force participation rate of Japanese women is low, so the impact of increasing this rate will be strong. The reason for Japanese women’s low participation rate in economic activities is the sharp constriction of the so-called M-shaped curve. The labor force participation rate of Japanese women forms an M shape, in which the rate temporarily falls between their late 20s and early 30s and starts rising again after child rearing is complete. For example, there is almost no constriction in the M-shaped curve in Sweden. In other words, if the constriction in the M-shaped curve can be eradicated, as in Sweden, Japan would be able to significantly increase the size of its labor force population.

Let’s make a simple calculation. Assume that the labor force participation rate by sex and age remains the same as it was in 2010. So, because the demographic onus will progress, the labor force population will decline by as much as 8,900,000—from 65,520,000 in 2010 to 56,620,000 in 2030. In this case, the ratio of dependent population will rise from 94.1 in 2010 to 103.5 in 2030. Next, assume the labor force participation rate of Japanese women by age rises to the level of Sweden in 2030. In this case, the labor force population will be 61,180,000, and the dependent ratio will be 88.3 in 2030. This time, the rate will be even lower than the figure in 2010. In other words, the demographic onus will be eradicated. Needless to say, it isn’t easy to achieve a labor force participation rate as high as Sweden; this calculation shows that the power of women’s participation can be quite significant.

Women’s participation and corporate management

Now, let’s look at this issue from the macro viewpoint of corporations.

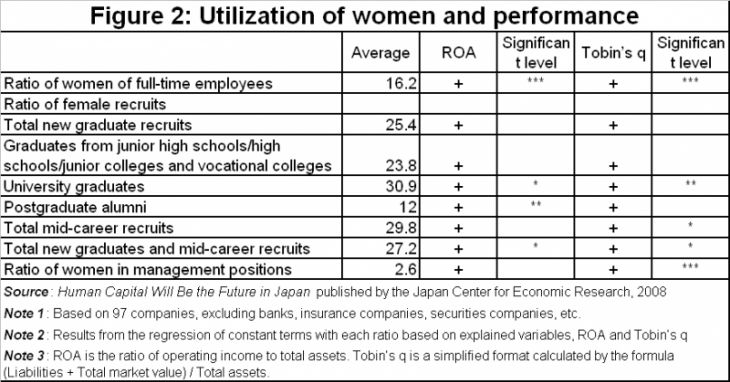

Figure 2 shows the analysis of the Japan Center for Economic Research, as mentioned above. This analysis was conducted as follows. First, the level of women’s participation (for example, the percentage of women among full-time employees and management positions) was determined through company surveys. Second, through financial reports, the return on capital (ROA) and Tobin’s q (a ratio of the value of a company’s assets to the total market value of its shares; the higher the figure, the higher the market evaluates the company’s future prospects) was obtained and examined. The results showed that companies that use women more extensively have greater profitability and future prospects (the more stars under “significant level,” the more significant the statistics).

In fact, this analysis, done in Japan, was not particularly new, and other similar surveys taken overseas show almost the same results. The statement that there is a positive correlation between the extent to which women are utilized and company profitability is almost an established proposition.

However, because this type of analysis only studies the relationship between these two indicators, it does not indicate the causal relationship. To obtain answers regarding this issue, our research proposes two grounds. First, women’s participation enables the development of better products and services. In a modern mature society, it is not only necessary for a company to achieve efficient production, but also to nourish its ability to offer new value to consumers while striving to differentiate itself from other companies. In such an environment, it becomes necessary to engage in product development and decision making from a variety of viewpoints, including those of women.

Second, companies in which women can continue to work without leaving are, in other words, companies that provide a pleasant working environment for their employees. That means that these companies are likely to have a pleasant working environment not just for women, but also for men. In other words, the percentage of women in a workplace is an indication of the level of stability of the working environment.

Whatever the reasons are, it has been confirmed, also based on factual evidence, that companies with a high degree of female participation are dynamic.

Women’s participation and the reform of work methods

Through the analyses described above, we have now learned that it is important both for the overall Japanese economy and corporate management to promote the employment of women. Despite this, the employment of women in Japan is low. I believe that this is related to Japanese work methods.

First, when the long-term employment system is dominant, companies tend not to spend job training costs on female workers as a core workforce, as there is a greater likelihood that they will leave the company in the future. When this happens, female workers also start thinking that they will never get a responsible job anyway, and often choose to stay home after getting married or giving birth.

Second, where an age-based remuneration system is widely accepted, the gap between wages for regular workers and non-regular workers is large, and wages for part-time workers are relatively low. In Japan, the chance of female graduates becoming full-time homemakers is higher than among women who graduated from high school. One reason for this is the fact that there is a greater likelihood that women with a higher education will get married to men with higher incomes. But it is also a reflection of the fact that there aren’t many part-time jobs in which women with higher degrees can use their abilities and earn a reasonable income.

Third, because Japanese employment is based on the assumption of long-term employment, employees tend to be occupied for long hours with corporate activities, such as overtime, the relocation of workplaces and corporate entertainment. This is also disadvantageous to women who have restrictions on their time.

As described above, there are aspects of the Japanese way of working that prevent women from participating in society. That is, the progress of women’s participation in society, unavoidable trends in the economy, and the traditional Japanese employment style fail to accommodate each other, resulting in women’s low level of participation in the labor force. This is the real malady, and the decline in the rate of women’s participation in the labor force is a symptom of this condition. Promoting women’s social advancement without remedying this problem will be very inefficient. I believe that, if the Japanese way of working is corrected, and an environment is created in which women can obtain jobs that are suitable to their abilities at each stage of their lives, women’s social advancement will automatically progress.

Growth strategy and the utilization of women

The government finalized its growth strategy on June 13, 2013. A review of this strategy shows that the government is also aware of the issues that this report has pointed out. For example, in “Reforming the employment system and reinforcing the capabilities of human resources,” the government set “Promoting the active participation of women” as its main agenda, and provided a policy outline. This included increasing the employment rate for women to resolve the M-shaped curve problem, developing a working environment in which it is easier for men and women who want to take childcare leave or choose part-time work to do so until their child is three years old, striving to eliminate childcare waiting lists, and encouraging all listed companies to appoint at least one woman as an executive officer. Regarding work methods, the government also pledged to change its policy from excessive employment stability to more fluid labor. The point is implementing this strategy. I hope that the government will steadily promote women’s participation in the economy in accordance with this strategy.

I would like, however, to make additional remarks about a point that is causing some concern. This is the policy of having childcare leave of three years. I oppose the promotion of this three-year childcare leave for the reasons described below.

First, at initial glance, a policy that allows workers to take childcare leave for a long period appears to be a friendly policy to women. However, it is questionable whether such a policy can really promote the employment of women.

From a company perspective, this policy makes companies regard female employees as people who may suddenly leave the workplace for three years. Under the traditional Japanese employment system, newly recruited graduates typically develop their careers at their companies. In this environment, female workers, who pose a risk of leaving their companies due to marriage or childbirth, have a disadvantage in their career development from the start, and a three-year childcare leave may even increase this disadvantage for them. So a three-year childcare leave may already hinder the entry of females even at their entrance point.

Second, an occupational gap of three years can also work against female workers themselves in terms of their career development. If the progress of their career is interrupted for a long three-year period, the benefit of a longer period of time spent exclusively on childcare may be overridden by the drawback of the deterioration of their career development. If a female worker tries to have a second child, this drawback will be even bigger. This is believed to be the reason for the fact that, at present, there are only a limited number of people who actually take the three-year childcare leave, even at those companies that offer this leave.

Third, the concept of a three-year childcare leave appears to reflect the values that a mother should dedicate herself to childcare for three years. This is based on the thinking that a child will not grow up soundly if its mother doesn’t take care of it for at least three years after its birth, and this thinking, often referred to as “the myth of the three-year-old child,” is believed to not be supported by factual evidence. Promoting the idea that mothers must raise their children for three years unnecessarily gives women a guilty conscience about starting work before their children are three years old, and makes them hesitant to go back to work.

It is important for the future Japanese economy to utilize women’s abilities. To do this, it is necessary to introduce support measures to enable women to manage their jobs and childcare concurrently. These measures, however, need to be based on the right judgments. Caution is necessary at this point, because wrong-footed measures will only have a negative impact.

Translated from “Tayona jinzai ga ikiru keiei-Josei no sankaku de kigyokeiei to nihon no keizai ga kawaru (How Management Can Make the Most of Diverse Human Resources — Increasing Women’s Participation Will Change Corporate Management and the Japanese Economy),” Shoko Journal, August 2013, pp. 14–17. (Courtesy of Shoko Journal)