The End of the Heisei Period: Striving to Become a Country that Takes Pride in Female Empowerment

Key points

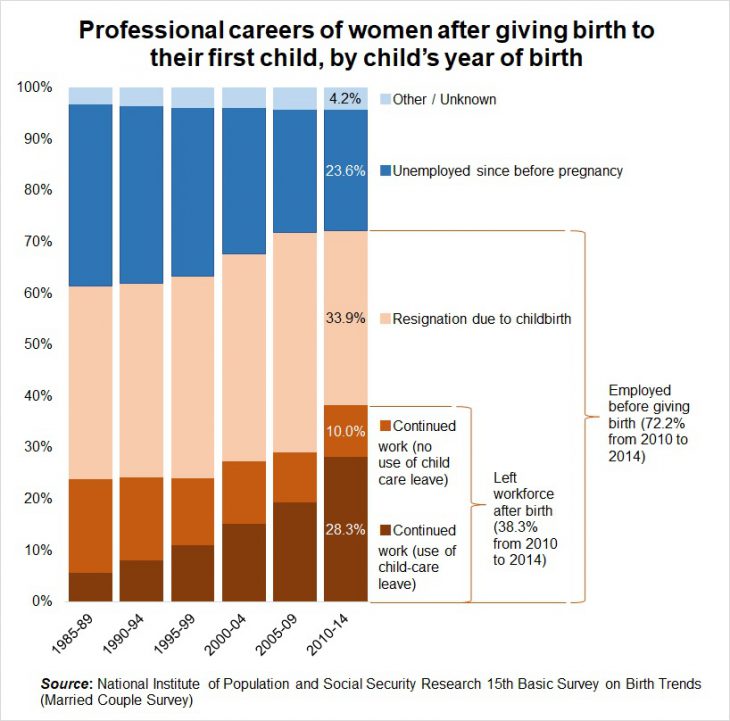

- Rate of women leaving the workforce after birth of first child continuing at a high level

- Importance of male participation and social support in the raising of children

- Despite progress in female empowerment, Japan lags behind other countries

Prof. Muraki Atsuko

The Act on Securing of Equal Opportunity and Treatment between Men and Women in Employment (the Gender Equality Act) was enacted in 1985, near the end of the Showa period. Today, more than thirty years later, female empowerment has again become the government’s most pressing issue, together with “work-style reforms.”

In this article, I would like to talk not only about how this is in itself an issue of crucial importance to society, but also how it plays a vital role in the context of dealing with Japan’s most serious social issue, that of the declining birthrate and aging population, as well as creating new value to which many Japanese companies are aspiring.

The Gender Equality Act came about to overcome strong objections from the business sector while riding external pressure in the form of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women implemented by the United Nations. Founded on the basic principle of allowing women to engage in full working lives without discrimination based on sex while respecting their maternity, the Act was designed to secure equal opportunity and treatment between men and women in employment.

In the years that followed, however, under the pressure and responsibilities women were owed to raise children or look after family members requiring care, it became increasingly clear that rather than leading flourishing working lives, many women were finding it difficult to continue working at all. In response, the Child-care Leave Act (revised as the Child Care and Family Care Leave Act today) was enacted in 1991, requiring employers to grant male and female workers child-care leave to look after children less than one year of age. And both “equality” and “balance” (between work and personal life) were established as a strategy for the empowerment of women.

In the years since, the Gender Equality Act and Child Care and Family Care Leave Act were progressively strengthened. Moreover, with the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace enacted in 2015, companies are now required to not only look at equality of “opportunity” but also verify whether they are developing women’s empowerment as an “outcome,” and are obligated to formulate and implement PDCA (plan, do, check, act) plans incorporating measures and target figures and to publicly disseminate the particulars.

Thanks to the enhancement of these measures to ensure equality and balance, slow but definite progress has been made throughout the Heisei period, including higher female employment rates and the proportion of female managers. Even so, some realities have a hard time dying out.

The percentage of women taking child care leave under the Child Care and Family Care Leave Act has continually exceeded 80% since 2007 but the same rate for men still languishes at between five and six percent. Even though the law applies to both men and women, the social construct that child-rearing is the role of women remains largely unchanged. Looking at the status of women who leave the workforce after giving birth to their first child, the percentage of those who stop working after getting married has steadily declined since the enactment of the Gender Equality Act. However, the percentage of women continuing to work after the birth of their first child remained between 20 and 30% until around 2010 (see chart).

Another serious problem has emerged in that period: the declining birthrate. The birthrate in Japan has continued to decline since the mid-1980s, and fell to a record 1.26 in 2005. The rapid advance of the declining birthrate and aging population spells an enormous burden for future generations. In addition, due to deteriorating government finance in response to ballooning social security commitments, the shift of the burden to future generations has already begun.

To prevent the impoverishment of society and economic collapse, and to form a society able to enjoy longevity in the era after Heisei, the only option is to increase the number of people of working age who contribute to social and economic activities. Can we increase the number of working women supporting today’s society and economy while at the same time increasing tomorrow’s working population?

The answer is clear if we look at the situation in other developed nations. Looking at data from member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), on the whole countries with a high level of female workforce participation also have high birthrates, and to the contrary, countries with fewer women working tend to suffer from a dwindling birthrate. In other words, societies that allow women to flourish are also societies that allow women to raise children as they desire.

What is the key to achieving this same outcome in Japan? The conclusion the Japanese government reached based on conditions in other countries and surveys of domestic needs was the importance of having men participate in child-rearing and society’s support for the raising of children. More specifically, this relates to work-style reforms that include men and the enhancement of childcare service.

There is no doubt that childcare service is a necessary condition for men and women with children to continue working. That is why some of the increased revenue from consumption tax hikes under the “comprehensive reform of social security and taxation systems” was allocated to childcare service, and over the past few years the development of childcare facilities has progressed at a rapid pace. This is an area in which we must not relent moving forward.

Next is the idea of work-style reforms. According to various surveys, the things that women with children consistently cite as conditions for continuing to work are shortening working hours in the entire workplace, an environment supporting a work-life balance, and flexibility in working hours. Overtime hours in Japan are long compared with global standards, and men take part in housework and child-rearing at a comparatively low rate. The time spent on housework and child-rearing by fathers with children before the age of elementary school averages a little over one hour in Japan, which is less than half of fathers in Europe and North America.

Studies have shown that households in which husbands spend more time on housework and raising their children show a higher percentage of wives continuing to work, along with a higher probability of giving birth to a second or subsequent child. This supports the supposition that situations where the wife is singularly responsible for raising children lead to a declining birthrate. On another front, greater participation by men in the raising of their children requires shorter working hours.

In June 2018, work-style reform-related legislation was enacted. The pillars of the legislation were the introduction of upper limits on overtime, a system for advanced professionals (post-hourly wage system), and promotion of the idea of equal pay for equal work. The legislation aims to correct extended working hours, facilitate the introduction of various flexible working styles, and develop rules to ensure that employees can receive equal treatment consistent with a diverse range of working styles. If these aims are achieved, male and female workers alike including elderly and disabled employees will be able to display their full potential through a range of working styles consistent with their individual capabilities.

Work-style reforms are not only about the health of workers; they are important policies designed to enhance the sustainability of society as a whole by allowing men and women to flourish in their jobs, to enrich domestic life, and to enable a diverse range of working adults to support society.

The direction of these policies, which have started as “female empowerment” and spread to work-style reforms targeting both men and women, is correct. But the problem is in the speed at which these reforms are taking place. The percentage of women who continue to work after marrying and giving birth to their first child started to increase from around 2010, but has still failed to break 40%.

In the “Gender Gap Index,” a measure of the level of equality between men and women published by the World Economic Forum, Japan ranks an incredibly low 110th out of 149 countries. What’s worse is that over the medium-to-long term, Japan’s rank has continued to slide. When we asked related international organizations why Japan’s ranking has fallen despite increased participation in society by Japanese women, the answer we were given is that “although Japan has improved, other countries have improved at a faster rate.” The same goes for efforts to address long working hours.

What should government do to accelerate these improvements? The answer lies in examining the progress of female empowerment and work-style reforms, analyzing the effects of government policy, clearly stating further measures and target values, and pursuing those initiatives while broadly disseminating the details about the Japanese populace. In other words, there is a need to implement the PDCA cycle that companies are required to operate under the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace. It is also time to consider the introduction of quotas in specific fields.

While female empowerment and work-style reforms are both important issues for Japanese society, what about on the level of individual companies? Many companies might still see these accommodations as “costs.” However, research suggests that companies with high percentages of female officers tend to enjoy more favorable business performance. In addition, companies that introduce work-life balance-oriented initiatives and flexible working hours see significant improvements in value-added productivity, even if it takes a while for those effects to become apparent.

The biggest challenge facing companies in the post-Heisei era will be the creation of new value. Achieving diversity in which women and a wide range of human resources can flourish will be a major driving force behind its realization. If more companies recognize this and tackle the issues in earnest, reform will increase in speed and a positive cycle between corporate growth and social growth will be produced.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 10 January 2019 under the title, “Heisei no owari ni (5): Joseikatsuyaku hokoreru kuni mezase (The End of the Heisei Period [5]: Striving to Become a Country that Takes Pride in Female Empowerment).” The Nikkei, 10 January 2019. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- female empowerment

- work-style reforms

- leaving workforce

- first child

- male participation

- equal opportunity

- Gender Equality Act

- Child Care and Family Care Leave Act

- work and personal life

- comprehensive reform of social security and taxation systems

- overtime hours

- Gender Gap Index

- Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace

- work-life balance