The Centenarian Companies that are Saving Japan―Tsumura, Konoike Transport and Seiren. Why did these companies survive?

Prof. Miyanaga Hiroshi

Japanese companies continue to face tough battles in the face of waves of globalization and digitalization. In particular, Japan is said to trail the pack in AI-related technology. When Japanese companies are compared to others around the world, a miserable situation is often recorded.

Turning our attention to within Japan however, today there are actually 34,394 “historic companies” that were founded 100 or more years ago (according to a 2017 study by Tokyo Shoko Research). Some researchers put the number at over ten thousand — notably more than in other countries around the world. In 2019, famous examples were Nintendo (over 130 years old), Morinaga (over 120 years), Olympus and NGK Insulators (both over 100 years). The oldest company in the world is an Osaka shrine and temple construction firm called Kongo Gumi. It was founded in 578 during the Asuka period. The oldest hotel in the world, as recognized by Guinness World Records, is the Keiunkan in Nishiyama Onsen, Yamanashi Prefecture. It was founded in 705, also during the Asuka period.

What is thought to be the oldest company in Europe, an Italian metalworking firm, was founded in 1369. America meanwhile, was founded at the end of the eighteenth century, so American companies don’t even enter the running.

But why does Japan have so many historic companies? What actions over the years have ensured they kept meeting consumer needs for so long? I believe that these companies offer many clues as to how Japanese companies can last through the current Reiwa period.

I have identified two sets of factors behind Japan’s large number of historic companies: external factors and internal factors.

I propose four external factors:

1) Lack of colonization

2) Huge changes to social structure

3) Long periods of peace

4) Existence of customers

Number two and number three may well seem to contradict each other, but I would like you to consider the Warring States period and the Edo period that came after. During the Warring States period, Oda Nobunaga instituted deregulation via his policies of free markets and open guilds and also encouraged the setting up of companies. Those companies then grew during the 270 years of peace that followed during the Edo period. Incidentally, many of today’s famous historic companies were founded around the time of the Meiji Restoration. Large numbers of new companies were founded during periods of great change such as the Meiji Restoration and the first and second world wars, before developing into historic companies during the stable periods that followed. This has happened repeatedly during Japanese history.

Next, I’d like to propose four internal factors.

1) Existence of business philosophy and family precepts

2) Personal qualities of owners (or adopted sons-in-law)

3) Tradition and renewal

4) Pivoting

First, let’s discuss the “business philosophy” of (1). Nidec Corporation is an almost half-century-old global precision motor manufacturer. At its establishment, Founder, Chairman and CEO Nagamori Shigenobu created a corporate philosophy, stating that “Nidec strives to promote prosperity of our society, our company and all our employees.” But when the global financial crisis happened, Nidec was expected to lose almost 10 billion yen a month, so one of its executives advised Nagamori that “surely, this time there is no alternative to layoff?” Yet, based on the company’s corporate philosophy, Nagamori did not lay off. Instead, he decided to convince all the company’s employees to accept an across the board 5% salary cut.

Nagamori didn’t stop there. After a while, the company’s performance recovered and he repaid employees the amount they had been underpaid over several months, along with interest at twice the standard rate.

He went back to a corporate philosophy based on the “prosperity of all [the company’s] employees” and got through a tough time without laying off any employees. Nidec had shown how the company respects its corporate philosophy, and the results weren’t limited to just reassuring employees at that time. If a similar crisis occurs in the future, the company’s employees will pull together because they trust Nidec as a company that respects its corporate philosophy — and so the company will go on.

It’s vital that the corporate philosophy continues to be respected even if the company’s leader changes. This is where the second factor, “adopted sons-in-law,” comes into play.

Under Japan’s old family system, if one’s son was not suited to heading the family business, one could take an unrelated but able young man as a husband to one’s daughter, make him the head, and continue the business. Thanks to this system, corporate philosophy was inherited down the generations and companies could continue to grow.

The third factor is “tradition and renewal.” This refers to constant renewal of a company’s technology.

Firstly, as a general rule, companies that stay in business for a long time have their own special technology and ideas as well as a corporate philosophy. This is “tradition.” If the company can skillfully renew this to fit each new era, it will become a historic company.

The term “open innovation” is popular these days. It’s a method by which companies strive to innovate through combining their own R&D technology with technology that already exists in the wider world. It may seem new at first glance, but it is something that machinery makers have done together with parts manufacturers on a daily basis.

Still, I believe that this recent trend for recommending open innovation is a dangerous one. When companies rely on other companies too much, their own technology becomes “hollowed out.”

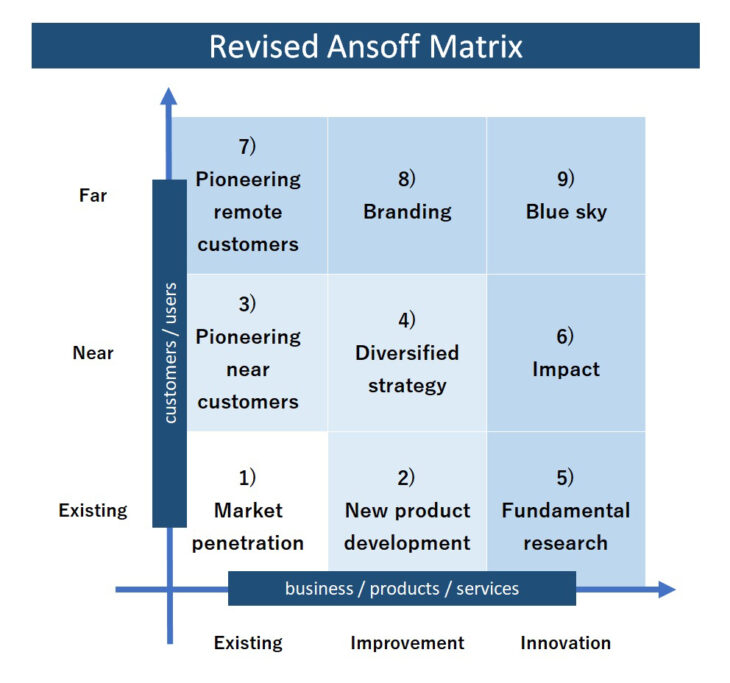

Furthermore, the real key is the fourth factor: pivoting. Please take a look at the diagram below. This is an Ansoff Matrix (a corporate strategic planning tool) to which I have made some additions. The horizontal axis shows company, products and services, and the vertical customers and users. Also, the diagram moves from existing to new from bottom left to top right.

A strategy aimed at selling new products and services to existing customers, for example, would move from square one to two (new product development).

The term “pivoting” originally comes from basketball. It is an action where a player keeps one leg in place and moves the other. Applying this to a company, one leg represents the company’s essential strengths and the other extension into new areas.

Generally, during pivoting, success is likely to occur when companies move towards the light grey squares above and right of one (the squares three, four, and two). Meanwhile, the dark grey squares outside these (five to nine) are “uncharted territory.” When companies don’t do things in order and instead jump straight into this uncharted territory, usually they fail. Why? Because they depart too far from their own strengths.

But companies that skillfully and repeatedly pivot then achieve persistent growth go on to become historic companies. I’ll explain this using several examples.

1) The “pioneering near customers” square: Tsumura & Co. (founded 126 years ago)

The well-known Kampo (was introduced from ancient Chinese medicine in the 5th century, but developed and adopted uniquely in Japan) company Tsumura began in 1893 with a Kampo pharmacy opened by Tsumura Jusha in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district.

Incidentally, Tsumura Jusha was raised in Nara Prefecture and was the second of three sons. In 1899, his older brother Yasutami founded Rohto Pharmaceutical in Osaka, the predecessor of Shintendo Yamada Anmin Pharmacy.

Tsumura had great success with its Kampo medicines and Bathclin bath salts. By 1991, it had grown to reach a turnover of 100 billion yen and 3,300 employees. With the collapse of Japan’s economic bubble however, its turnover dropped dramatically. Generally, pharmaceutical businesses tend not to be affected by the larger economic climate, but the company’s main business was hampered by slowdowns in the business of subsidiaries completely unrelated to its main business, such as the import and sale of beauty products. During the quarter ending March 1994, the company booked losses of 2.1 billion yen and its third consecutive loss.

Additionally, R&D into new non Kampo drugs begun during the time of the company’s third CEO worked against it. The company had departed from its Kampo forte. Also, since it was selling these new drugs to doctors who were not existing Tsumura customers, this strategy was an attempt to target high-risk “uncharted territory.” Such business activities risk a typical pattern of failure where, from within the company, they seem like innovative and fresh initiatives, but in reality are uncompetitive and unoriginal. Tsumura was no exception.

To rebuild its business, Tsumura brought in Yoshii Junichi of Daiichi Pharmaceutica (now Daiichi Sankyo.) Yoshii reworked the company’s business strategy to focus on specializing in Kampo and selling to new customers who had not prescribed Kampo before (i.e. doctors who had studied Western medicine). He set a target of breaking out from square one to square three (pioneering near customers).

This policy of ending development of new drugs and specializing in Kampo provoked fierce opposition from researchers who feared job cuts. But Yoshii gave them a new mission; he asked them to explain scientifically why Kampo is effective. Then based on that evidence, he instructed the company’s sales and medical representatives to visit doctors they hadn’t before. He also decided to invite interested doctors to seminars run by specialist Kampo doctors. An ingenious tactic was to charge for the seminars. His idea was to invite motivated doctors who would take part even if they had to pay a fee. Yoshii’s strategy even ended up reforming university medical department education and clinical departments. He cooperated with creation of curricula and the writing of textbooks for education in Kampo. Today, all eighty Japanese universities with medical departments teach Kampo and it has also become a subject in the Examination for Medical Practitioners.

As a result, the market for Kampo itself has expanded and Tsumura’s share has also increased. By the quarter ending March 2009, revenue had recovered to 90 billion yen (consolidated) and even 88.4 billion yen by non-consolidated accounting. Its operating profit was 16.4 billion yen (consolidated) and 18.8 billion yen (non-consolidated), the largest profit since the company was founded.

Today, medical-use Kampo pharmaceuticals account for 95% of Tsumura turnover and the company has an 84% share of the Kampo market. It has become the overwhelming leader in its field of expertise; an excellent example of deciding to clearly pivot (towards Kampo) and, what’s more, succeeding in pioneering near customers.

2) The “new product development” square: Konoike Transport (founded 139 years ago)

There is a company called Konoike Transport that was founded in Osaka in 1880. As its name suggests, this company’s business is based on logistics and distribution. Meanwhile, it has expanded its business activities to a wide range of related areas.

Please imagine a Japanese airport check-in counter. You are probably picturing the ground staff who handle check-in procedures for passengers. Although these staff wear airline uniforms, they are actually employees of the Konoike Transport Group. Originally, Konoike Transport was only responsible for transporting customer baggage from the check-in counter to aircraft, i.e. logistics services. It is efficient, however, for the same staff to handle everything from check-in procedures to transporting baggage to aircraft, making the costs for airlines lower; and it is convenient for passengers too. Having realized this, Konoike Transport proposed a combined service covering counter operations and baggage transport to their existing airline customers. In other words, they pivoted to square two (new product [services] development).

What’s more, in 2010 when JAL’s business ran into trouble, Konoike Transport bought one of JAL’s companies, K Ground Service Co., Ltd. It expanded its business activities to cover all airport ground services, including lounge operations, aircraft marshaling and baggage handling.

Starting from logistics, it moved out into other related business activities. Bringing these combined services together and offering them is part of Konoike Transport’s combined solutions business model. Today, such combined solutions account for around 70% of Konoike Transport’s turnover. Its logistics business is no more than 30.6% (as of March 2018).

I’d like to introduce one more example of Konoike Transport’s combined solutions. At the same time as starting its airport business, Konoike Transport entered the medical sector, providing services to recover used hospital medical equipment. In other words, it provided new customers with its existing logistics services, an example of square three (pioneering near customers).

The unique aspect is what follows. At the time, nurses cleaned and sterilized used medical equipment within the hospital. But with a shortage of nurses, this became a considerable burden on hospitals. Having noticed this, Konoike Transport started an add-on service collecting medical equipment, cleaning and sterilizing it at its facility, then returning it to the hospitals.

In order to provide a new service (square two) to the same customers (nurses and hospitals), it’s vital to rapidly work out what issues customers face. Then, making solution of those issues the target destination of the pivot will lead to new business opportunities.

In fact, Konoike Transport was a latecomer to proxy services in the medical sector; yet, today they occupy the top spot in the sector. How can that be? Konoike Transport offered other companies in the industry the management system it had set up for recovery, cleaning and sterilization of medical equipment services. Then, the system became the industry standard.

Additionally, Konoike Transport conducted M&A activities. A reason that effective synergies are difficult to achieve with M&A is that it’s hard to combine different systems. But if different companies in the same industry use the same system, the obstacles are easily overcome. As a result, Konoike Transport took the top market share.

What’s more, Konoike Transport’s pivot wasn’t limited to improving services. It moved on from cleaning and sterilization add-on logistics services outside hospitals to logistics services within hospitals. It suggested handling sterilization services and, in the process, making use of empty hospital spaces as logistics centers. Representative Director & President and Chief Executive Officer Konoike Tadahiko says that, “Konoike Transport’s greatest strength is having a presence in the manufacturing process.” Because of that, it knows the timing and location of customer needs and can offer not only logistics, but also one-stop services that even include storage, ordering, and resupply. That’s of great value to customers. Consequently, such combined solutions are more profitable that logistics operations.

For a historic company to keep going over time, it needs to move its pivot foot. That’s because sometimes the business area where it has placed its pivot foot declines as demand changes. Probably, Konoike Transport is no longer perceived to be a “transport” company. Its pivot foot is placed in “providing solutions.” It moved from square 2 to square three, relocated its pivot foot, and expanded its range of customers and services.

3) The “diversified strategy” square four: Seiren (founded 130 years ago)

Today’s Seiren was established in 1889 in Fukui Prefecture, a region of Japan with a flourishing silk industry. The company’s name comes from a Japanese term referring to the process of removing impurities from silk fabric.

As the textile industry flourished during the Showa period (1926 to 1989), Seiren was one of Japan’s most famous companies. Yet, at the same time as cheap imported textile products started to appear from the beginning of the 1980s, the strong yen affected its business, and the company was at risk of going under.

In the middle of this crisis, Kawada Tatsuo was appointed the company’s first CEO from outside the founding family. Kawada completely changed the company’s existing subcontractor business model and moved into dyeing and processing both upstream and downstream in the industry supply chain. Eventually, he even made bold and ambitious moves into areas outside textiles. His target was square four (diversified strategy); that is, selling new products and services to entirely new customers.

When Kawada joined the company in 1962, it could make sufficient profits simply as a subcontractor to manufacturers, dyeing cloth as instructed. For that reason, when he urged the company’s top executives to change that business model, the reaction was not good.

So Kawada set out to develop new business by himself. He investigated whether business using the company’s own-developed technology and close to end consumers might be possible. He visited textile-related companies one by one and worked on new product development in the factory at night when no managers were around. And one of the businesses he arrived at was car seats.

Car seats at that time were made from PVC and quickly deteriorated. Although there was a latent need to switch to slightly more durable products, the car industry of the time took it for granted that seats would rip and fade in color within a decade.

So Kawada started by buying machines that could weave and knit, then set up a separate company for a car seat business.

His thinking was that, if the company took on the whole manufacturing process from original thread to sewing and avoided inefficiency and waste in all those manufacturing tasks, it would surely make a profit. They could shorten delivery times… and because shorter delivery times would benefit the company’s automobile maker customers, Seiren wouldn’t just be a processing supplier, but could achieve equal footing as a business partner.

The result was that he succeeded in developing new car seats. Just as Kawada had intended, the business grew healthily; today, it includes all Japan’s car makers among its business partners, and it has a market-leading share of 40%.

When Kawada eventually became Seiren CEO, he established a fresh managerial strategy based on digitalization, direct distribution, moving out of cloth and textiles, globalization and corporate structural reform. He also started to work on developing various new products. At a glance, this strategy might seem like a reckless one that departs from company strengths to uncharted territory, but the pivot point that Kawada had in mind for Seiren was the “whole manufacturing process from original thread to sewing” that he’d achieved with car seats. Using this method, Seiren successfully reduced costs across the board and shortened delivery times, to the great appreciation of its trading partners.

What’s more, as it combined its various production processes, Seiren also developed new inkjet textile printing technology. Thanks in part to this new technology, today Seiren has expanded its business into five areas: automotive (centered on car seats), fashion, housing, electronics and medical.

Using its own-developed inkjet textile printing technology it speedily delivers one-off jeans to individual consumers. In the electronics field, it has commercialized a textile mesh for use as electromagnetic shielding on the front of plasma screen televisions. In the medical field, it has employed technology belonging to a textile operation purchased from Kanebo to commercialize artificial blood vessels used as arteries. These have the special characteristics of being easy to suture (since they are textiles) and not being rejected by the body’s cells.

Seiren has made use of its “whole manufacturing process from original thread to sewing” to perfect its own unique advantages and gain an unassailable lead over competitor companies. Surely the result of an excellent pivot to meet the needs of customers and the time.

Tomorrow’s historic companies

Finally, I’d like to introduce two firms with the potential to live through the Reiwa period and go on to become “historic companies.” The first is Iris Ohyama. This company sells a wide range of products, household electric appliances, LED lighting, cooking goods and even rice, mainly in home improvement stores. As its main products constantly change, people often feel that it is hard to get a handle on the manufacturer’s business.

Iris Ohyama was founded in 1958 in the city of Higashi-osaka by Ohyama Morisuke. Last year, it had its 60th anniversary. Initially, it made plastic products and was called Ohyama Blow Industry. But five years after its establishment, Morisuke was diagnosed with cancer. At the time, his son Kentaro was in the third year of high school. Kentaro abandoned his plans to go to university and took over the family business of five employees, five million annual sales, and small city factory that fulfilled orders for their clients. As Iris Ohyama’s second-generation president, he built it up into a large company and is now its Chairman. Although he was appointed president at nineteen years old, this was the high-growth period and job after job came to the company. Ohyama, however, was hit by the 1973 oil crisis. The funds that the company had built up over ten years disappeared in just two and one of its two companies was closed. Half of its employees were laid off.

After the end of the bubble in 1991, Iris Ohyama drew up a corporate philosophy. It began: “Our company’s aim is to continue forever. We must establish a structure that can produce profits whatever the conditions of the time.” Ohyama vowed to never again to go through the painful experience of laying off employees, determining to “do business not losing money during bad conditions rather than making profits in good conditions.” Setting a corporate philosophy like this has something in common with historic companies.

Through painstaking research, Ohyama realized that products bought through household spending are less likely to be affected by a bad economy than manufacturing materials or industrial products. He purchased a database of some 140,000 companies and as a result of his research arrived at the idea of garden products.

As Ohyama had predicted, the garden products were a huge hit. But as the products sold and the company increased production a problem arose: wholesalers weren’t able to keep up and there were shortages on home improvement store shelves. So to deal with this, Iris Ohyama elected a maker-vendor business model where they both manufactured products and acted as their wholesaler. They launched a sales system where they delivered products directly to home improvement centers without any wholesaler intermediary.

Because of this, Iris Ohyama’s customers changed from wholesalers to home improvement stores (retail stores) (see square three).

What’s more, Ohyama started developing all sorts of everyday products, not just gardening supplies. Today, Iris Ohyama produces some 1,000 new products each year, accounting for more than 60% of its revenue. But why does it create so many new products? This strategy was the result of selling directly to home improvement stores and getting a more precise hold on consumer-level needs. When the economy goes bad and things stop selling, home improvement and other stores are constantly seeking new products. With lots of new products, Iris Ohyama would be able to fill a large section of store shelves.

At the company’s regular Monday new product development meetings, Ohyama and other executives turn out in force and review almost 100 products. From morning to night, prototypes are displayed, staff give presentations, and members discuss how the new products are different to existing Iris Ohyama products and to competing products. Then decisions are then made whether to bring the products to market.

Prices are carefully set to produce a profit, with a sales price that can deliver a 10% profit margin decided in advance. The company does not manufacture products when it cannot ensure a 10% profit margin and it doesn’t discount from the decided price. So that products can still go up against competitors’ goods, Iris Ohyama even manufacturers metal molds, nails and screws in house. Staff responsible for developing products themselves calculate and include part purchase, manufacturing and even distribution costs in their proposals.

What’s more, since 2001 Iris Ohyama has dispatched its Sales Aid Staff (SAS) to around 1,000 outlets across Japan where they explain products to customers on the store floor. The SAS ask customers about any dissatisfaction with products and desired functions. That information is then collected and sent to head office. Some 80,000 items of feedback are collected a year, then used to develop new products (square two).

The second company is Muji (Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd.) In April 2019, Muji launched a flagship store in Tokyo’s Ginza district and it has opened its first hotel in Japan, qualities that suggest potential to become a historic company.

Muji started out as a private brand of Seiyu in 1980. In line with its brand slogan “lower priced for a reason,” by reducing marketing costs it was able to offer inexpensive goods. Muji started out with stationery and everyday goods, attracting admiration and a growing fanbase for is inexpensive and simply designed, yet good quality, products. Today, Muji has even expanded its business to homebuilding and hotels, selling to this core customer base (square 2).

I recently visited one of Muji’s new restaurants, Café&Meal Muji, where I found a healthy menu and many female customers. Because the business is rooted in customer demand, even when it broadens its product range, it is still supported.

Learning from the wisdom of historic companies

Philip Kotler is a famous American marketing authority. During the 1970s, Yoshida Tadahiro, the former chairman of YKK, travelled to the United States to study at his business school. Apparently, after one seminar Kotler called Yoshida and asked him this: “Why have you come from Japan to study in the United States? Surely, Japan is a treasure trove of marketing expertise?”

Japan’s historic companies hold many hints as to how companies can develop and grow in the long term; not just in marketing, but also business models and overall business strategy. One famous example is when, in the early Edo period, the Mitsukoshi department store switched from selling on credit (common sense at the time) to cash sales. Recently however, there is a trend for European and American management to be popular. But European and American business philosophies certainly aren’t perfect in every aspect. For example, one of Wall Street’s faults is look at accounts via the fourth quarter account. This focus is just too short-term. When there’s no profit restructuring is called for; and when a company is profitable there are demands to cough up money for stockholders. Rather than increasing research and development funds, companies have to return money to stockholders, and saving money up is seen as wrong. But what happens when these stockholders are short-term, only keeping their stocks for five years or so? Isn’t it an important responsibility of companies to sustain their businesses over the long-term, and to give profits not just to their stockholders, but their customers and employees too?

There are things we should learn from European and American management techniques. But first we must take a fresh look at the wisdom that our predecessors have collected and stored in Japan’s historic companies.

Translated from “‘Hyakunen kigyo’ ga Nihon wo sukuu ― Tsumura, Konoikeunyu, Seiren, karera wa naze ikinokotte koretano (The Centenarian Companies that are Saving Japan―Tsumura, Konoike Transport and Seiren. Why did these companies survive?),” Bungeishunju, August 2019, pp. 330-339. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [August 2019]