The Way to Revitalize Japan’s Economy: The Government Should Not Intervene in Prices and Business Activities

The author points out that “private financial institutions can provide a large part of both pension and medical insurance. There is also an aspect of the current social security system in which the government is crowding out these private businesses.” To revitalize the Japanese economy, the privatization of social security should be promoted, which “will also lead to a higher structural economic growth.”

Photo: Luce / PIXTA

Key Points:

- Structural economic growth cannot be lifted by fiscal and monetary policies.

- Price controls through subsidies, etc. result in huge fiscal expenditure.

- Promote privatization of social security to harness the vitality of the private sector.

The public is clamoring for this or that measure to revitalize the Japanese economy. However, many of these measures are unnecessary and may even create obstacles.

Fiscal and monetary policies designed to stimulate the economy do not have the effects that the public generally believes they do. A review of economic research shows that these policies have had some success in providing support during business cycle downturns. However, their effects are strictly limited to business cycles as defined by economists. Such downturns do not occur as frequently as the public perceives.

Real gross domestic product (GDP) typically zigzags and rises slowly over time. The average straight line (trend) shows the structural economic growth. It is a moving average over a fairly long period of time and can change gradually. Meanwhile, the business cycle, as defined in modern economics, moves up and down around the trend. A business cycle downturn means that the economy has entered a downward phase around the trend. In Japan, the Cabinet Office determines the phase of the business cycle.

During the Abe administration, Japan experienced its second-longest economic expansion – an upward trend – since World War II. Nevertheless, many voices in the public claimed that they were not feeling the benefits of this economic expansion. In response, the government and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) maintained fiscal deficits and continued monetary easing for an extended period. This approach must be viewed as a mistake. In principle, fiscal and monetary policies during a boom involve running a budget surplus and raising interest rates, the opposite of what should be done during recessions.

However, the primary focus of monetary policy is on price stability rather than economic stimulus. Regardless of the state of the economy, it makes sense to ease monetary policy until an inflation target of around 2% is reached. But, running a budget deficit in good times is strange.

At a deeper level, the public’s dissatisfaction with the economy is likely due to their perception of a boom as average economic growth rather than a business cycle phase as defined by economists. In fact, even during the prolonged economic expansion under the Abe administration, the average economic growth was lower than in Japan’s high-growth period or the bubble period as well as that of China’s rapid growth period since the 2000s.

However, research on economic growth has shown that, in the process of developing countries catching up with advanced countries, their economic growth is usually higher than that of advanced countries. In this sense, it is not appropriate to compare Japan during its high-growth period or China in recent years with Japan in the past 30 years or so after it became an advanced country.

Moreover, if economic policies are not supported by economic knowledge, that is, theoretical and empirical research, their effectiveness will be unclear and they may even run the risk of producing side effects. In times of economic expansion, economic restraint is more necessary than economic stimulus.

However, what is truly needed is not economic measures to counter business cycles, but policies to promote medium- to long-term structural economic growth. Research so far clearly shows that fiscal and monetary policies for countering business cycles do not contribute to this goal. What is effective are structural reforms that unleash greater private sector dynamism. The only way forward is to identify structural problems and improve them to ensure that the market economy functions effectively.

◆◆◆

Japan has a variety of structural problems, but the one that comes closest to fiscal and monetary policies is government intervention in various prices and business activities.

Western central banks tightened monetary policy for the past few years in response to inflation that reached around 10%, triggered by the rise in international energy and food prices following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and the beginning of the Ukraine crisis. Now that inflation is finally under control, they started to ease monetary policy.

Japan is highly dependent on foreign sources of energy and food, but consumer prices have been kept low compared to Europe and the United States. Unlike Europe and the United States, the BoJ has moved little until recently, so the low inflation is not the result of a tight monetary policy.

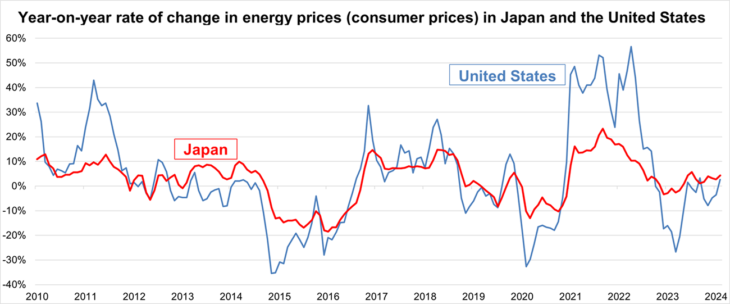

One reason is that food prices, such as rice, wheat and milk, and energy-related prices, such as electricity and railways, are to some extent publicly administered. In addition, fuels such as gasoline are actively subsidized, which keeps price fluctuations in check (see chart). Therefore, inflation has been lower than in Europe and the United States over the past few years. As a result, the BoJ has continued to ease monetary policy.

Source: Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Comparison of items corresponding to city gas, propane gas, kerosene, and gasoline in Japan and the United States

However, this price control through government administration and subsidies, which seems to stem from a popularity contest, also involves considerable fiscal expenditure. In Japan, which has a structural budget deficit, this has been covered by further issuance of government bonds, which have been absorbed mostly by the BoJ as part of monetary easing. Although the BoJ purchasing is done through the secondary market, it cannot help but be indirectly criticized as monetary financing (filling the budget deficit). This series of irregular policies is said to be one of the causes of the sovereign debt crisis that occurred in other countries, and is considered taboo in economics because it damages the foundation of economic growth, which is a free market economy.

Regarding interventions in economic activities, the government appears to have a subsidy culture that places absolute importance on the survival of small and medium-sized enterprises. This creates zombie firms, trapping labor and capital in low-productivity enterprises and preventing their more effective use. In addition, industries such as semiconductors have been heavily subsidized in recent years. Import-substitution industrial policies, such as the national car concept implemented in Latin America until about 1980, are known as a huge failure. Will Japan adopt such a policy?

Behind this policy, there may be a logic: Japan should do the same because other countries around the world are actively promoting industrial policies using subsidies. But, this is a situation called a “prisoner’s dilemma” in game theory.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) once created an international framework to curb the race to lower corporate taxes. By the same token, an international framework to curb subsidy competition is needed. Such a mechanism already exists in the European Union (EU) and is being discussed at the World Trade Organization (WTO), but has not made much progress. Japan, which is the most indebted country in the world, should take the international lead in curbing wasteful subsidy competition.

◆◆◆

The core of the budget deficit is social security, especially pension and medical expenses, a large share of which goes to the elderly. The current system, which was introduced around 1960, was designed by the government to take responsibility for caring for the elderly at a time when the generation heavily affected by the turmoil of the war and postwar period could not even think of saving for retirement. Today’s working generation, however, lives in an era when individuals can prepare for retirement on their own.

On the other hand, private financial institutions can provide a large portion of both pensions and medical insurance. In some ways, the current social security system is crowding out these private businesses. To improve the quality and quantity of these services in an aging society, we should make effective use of the vitality of the private sector, which will also lead to higher structural economic growth.

If the current level of social security at public expense is to be maintained, taxes and social security contributions will have to be increased to cover the deficit. If the national burden, which has already reached about 50% of GDP, is further increased, Japan will fall deeper into a “debt overhang” situation that will undermine people’s motivation to work and companies’ incentives to invest. Then, the structural economic growth will continue to decline. Therefore, in order to avoid further tax increases, we should proceed with the privatization of social security as far as possible.

It is often said that the fall of Rome, which once boasted of its glory, was due to the fact that people started asking politicians for bread and circuses. Aren’t Japan’s social security, various subsidies, and price controls the bread and circuses of today?

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 4 October, 2024 under the title, “Nihon Keizai Saisei e no Shinro (II): Kakaku, Kigyo Katsudo ni Kainyusuruna (The Way to Revitalize Japan’s Economy (II): The Government Should Not Intervene in Prices and Business Activities),” The Nikkei, 4 October, 2024. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Ueda Kenichi

- Center for Advanced Research in Finance (CARF),

- Graduate School of Economics

- Graduate School of Public Policy

- University of Tokyo

- fiscal policy

- monetary policy

- structural economic growth

- price control

- subsidies

- subsidy competition

- price fluctuations

- social security privatization

- pensions

- medical insurance

- privatization

- inflation

- national burden

- debt overhang

UEDA Kenichi, Ph.D.

UEDA Kenichi, Ph.D.