The 1993 System and the “rule of 3:2:1”: How can Japanese politics regain a competitive rivalry among political alternatives?

Having seen the political turmoil over the past 30 years in Japan, the owl of Minerva is set to take its flight in search for a framework to understand it. Japanese politics in the Heisei era, which aimed to establish a two-party system, is now characterized by a tripolar structure. Which political force will adapt to the new era and take power?

Ohi Akai, Adjunct Lecturer, Hiroshima Institute of Technology

Lecturer Ohi Akai

Thirty years have passed since the political realignment in 1993. Having seen the political upheaval over the last three decades, the time has come to analyze contemporary political history, and the owl of Minerva is set to take its flight.

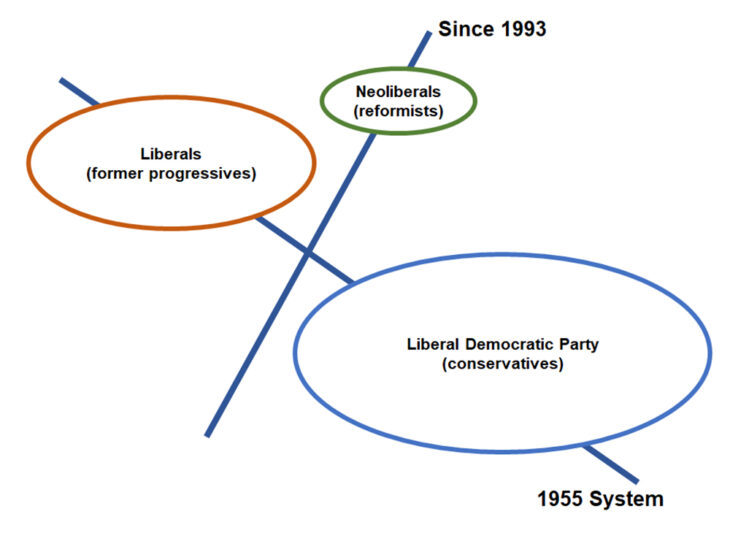

In this article, I propose a framework to understand contemporary Japanese politics through the following three issues. First, the 1993 political realignment and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) split shifted Japan’s political confrontation from a dichotomy of “conservatism vs progressivism” to a tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals” (1993 System). Second, in current Japanese politics this tripolar structure comprises the “LDP and Komeito coalition/opposition parties (Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan [CDPJ], Democratic Party for the People [DPP], Social Democratic Party [SDP], Japanese Communist Party [JCP], Reiwa Shinsengumi [Reiwa])/Japan Innovation Party [JIP],” with power relations among these parties in a ratio of 3:2:1 (“rule of 3:2:1”) throughout the 2010s. Finally, I conclude by investigating the conditions for a potential regime change based on the policy characteristics and support bases of the three blocs.

Tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals”

Since the political reform of 1994, Japanese politics has been expected to shape a two-party system that allows for change of government on a regular basis. However, while the LDP held one-party dominance up to the 2022 Upper House election, opposition parties have still been broadly divided into the JIP and parties derived from the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which gives Japanese politics a cumbersome tripolar structure.

In a paper published in the early 2000s, political scientist Hirano Hiroshi (professor at Gakushuin University) described the tripolar structure in Japanese politics of the 1990s. According to Hirano, “neoliberals” who advocate privatization, deregulation, and administrative reform emerged in the 1990s and they provided a new political choice in addition to the conventional confrontation between “conservatives vs progressives” over constitutional reform and security matters. This resulted in a tripolar structure based on policy preferences, with the traditional “conservatives” and “progressives” being joined by the “neoliberals.” Voters’ policy preferences for each of the three forces are also distributed quite evenly, albeit with some variations. This structure identified by Hirano has ultimately dominated Japanese politics over the past three decades, starting around the 1990s and continuing up until the present day.

Clearly, the tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals” in Japanese politics can be traced back to the political realignment of 1993 and the emergence of “non-LDP conservative reformists.” The LDP split resulted in the emergence of three new conservative parties, the Japan Renewal Party (JRP), the Japan New Party (JNP), and the New Party Sakigake (Sakigake), which adopted “reform” as their rallying slogan to change the status quo in the post-1955 era.

These three new conservative parties may be referred to collectively as “non-LDP conservative reformists.” While these parties were “non-LDP” as their name suggests, they were essentially “conservatives” not “progressives (socialists),” and they chose the word “reform” to tackle the old LDP hegemony. These reform-oriented conservative parties denounced traditional bureaucratic politics and money-oriented politics driven by vested interest, calling for the reduction of public works projects, deregulation, and decentralization.

According to political scientist Kabashima Ikuo (professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo), those who voted for the three new conservative parties in the Lower House election in 1993 were voters who were moderate in ideology but conservative-centrist leaning, dissatisfied with LDP politics and feeling the need for regime change. For voters of the post-Cold War era who were not radical enough to desire the socialism of the “progressives” but were dissatisfied with the long-standing one-party “conservative” rule, the “non-LDP conservative reformists” emerged as a new alternative that suited their interests and values.

Economist Masamura Kimihiro (professor emeritus at Senshu University) expressed the quintessential image of the tripolar structure of the 1990s as follows. “Conservative” was linked with conventional bureaucratic politics involving stop-gap measures to get through difficult situations, without addressing the real flaws of the Japanese socio-economic system. The “progressives” on the other hand continue to pursue an outdated vision of a socialist revolution. In contrast, the “reformists” were the only effective alternative to launch the structural transformation of economic and social systems in post-Cold War Japan.

Attempt at the two-party system and reality of the tripolar structure

The political realignment of 1993 produced a tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals.” At the same time, 1993 marked the beginning of the “Heisei Democracy” that sought to establish a two-party system through a single-member constituency system. What is the relationship between the attempt of the “Heisei Democracy” to artificially create a competitive two-party system and the reality of a tripolar structure rooted in a civil society?

It must be remembered here that, while the primary focus of political reform was exclusively to create a competitive two-party system, the ideological nature of the two major parties has not been clear and left open to interpretation by political pundits and politicians. As such, when it came to the process of introducing a single-member constituency system and the kind of two-party system that would follow, the political elites were strange bedfellows.

For example, Ozawa Ichiro (former Secretary-General of the LDP, who left the LDP in 1993 and founded the JRP; currently a member of CDPJ), who led political reform, imagined a “two conservative party system” resulting from the bloating and fragmentation of the LDP. According to Ozawa, if elections were held under a single-member constituency system, the LDP would gain approximately 400 seats. The LDP would then implode and the external movement for political renewal stimulated by the LDP disruption would lead to the reorganization of opposition parties, resulting in a shift to a two-party system. At the time, Ozawa seemed to think he could wield his influence to create Japanese politics as he wished to picture it.

The commitment of political scientist Yamaguchi Jiro (professor emeritus at Hokkaido University) to political reform was predicated on anticipation of a two-party system of “conservative vs center left” modeled on the British Conservative Party and the Labour Party. Yamaguchi had long argued for the Social Democratic Party of Japan (SDPJ) to adopt a pragmatic approach, and it is well known that after the founding of the DPJ he was an enthusiastic proponent of the liberal bloc within the DPJ.

On the other hand, Uchida Kenzo (1922–2010, served as political director of Kyodo News, professor at Hosei University) of the Committee for the Promotion of Political Reform was of the view that the confrontation in single-seat constituencies would be a three-way struggle among “the LDP vs independent conservatives vs progressives,” with one of the parties being selected in a series of Lower House elections and the remaining two parties forming a structure akin to the British Conservative Party vs Labour Party, or the American Republicans vs Democrats.

In each of these scenarios, while all insisted the single-member constituency system results in a two-party system, both the process of arriving at that result and the nature of the two party system were diverse and intertwined.

As Uchida pointed out, Japanese politics following political reform in 1994 has been a three-way battle among “LDP vs independent conservatives vs progressives.” However, despite the fact that there have been nine Lower House elections under the single-member constituency system since 1996, the number of political choices has never been reduced from three to two. Under a system that aims for two parties, neither political parties nor voters are able to converge political options into two major parties, and a tripolar political structure endures.

Political scientist Masumi Junnosuke (1926–2010, professor emeritus at Tokyo Metropolitan University) designated the political equilibrium established in 1955 “the 1955 System.” Masumi described the 1955 System as a grand political dam into which several rivers flowed, creating static stability. According to Masumi, an even larger dam would be built in future, but until then politics are contained within the dam of the 1955 System.

As expected, in 1993 the dam burst and a torrent of water released. In the current of the rampant flood, however, we can see a certain pattern emerge over the past thirty years. Since 1993, Japanese politics has been encapsulated as a tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals,” though the political parties that embody those labels have shifted. In terms of policy characteristics and power relations, albeit with some notable exceptions, this tripolar structure has not changed significantly to date. As a political scientist, it is difficult for me to overcome the temptation to follow Masumi’s “the 1955 system” and designate this tripolar structure of “conservatives/former progressives/neoliberals” the “1993 System.”

“Rule of 3:2:1”

Since 2012, the power relations of the tripolar structure have been virtually fixed, with the “liberals (former progressives)” and “neoliberals (reformist)” pitted against the LDP, which holds the “conservative” position.

The 2021 Lower House election was expected to be a one-on-one contest between the LDP and the opposition bloc of the CDPJ and the JCP, which managed to unify candidates in a single-seat constituency. Electoral cooperation among opposition parties made speculation possible that the Japanese party system would finally converge into two major parties, the LDP-Komeito bloc and the CDPJ-JCP bloc. Contrary to expectations, however, the CDPJ and JCP lost ground, while the LDP maintained its position and the JIP increased its seats to 41. This result suggests that the public opinion in Japanese civil society still firmly support “reformists.”

The neo-liberal JIP was expected to make further strides in the 2022 Upper House election. However, in the face of the stable victory of the LDP-Komeito, the JIP was still unable to expand its area of influence beyond the Kansai-centered region, resulting in the continuation of a tripolar structure in which two opposition parties stand against the victorious LDP-Komeito bloc.

When it comes to the number of votes in the proportional-representation constituencies in the 2022 Upper House election, the LDP-Komeito bloc has 24.44 million, the opposition parties (CDPJ, DPP, SDP, JCP, Reiwa) have 17.13 million and the JIP has 7.85 million. The ratio of these votes obtained by three blocs is “3:2:1”, and throughout the 2010s, these power relations did not undergo any significant shift. In other words, the number of votes in the proportional-representation constituencies in the eight national elections since the Lower House election in 2012 is another indicator that the power relations in this tripolar structure have remained stable, so much so that we can refer to the “rule of 3:2:1.”

Tripolar structure of contemporary Japanese politics

“Two opposition parties” under a centrifugal force

The persistence of the tripolar structure of “LDP-Komeito/opposition parties/JIP” may be attributed to the fact that these three political blocs have surely represented the policy and values of each social cleavage in Japanese civil society. Below, I identify the policy characteristics and support bases of each of the three forces.

The policy characteristics of the opposition parties bloc led by the CDPJ in the 2021 Lower House election can be summarized by three agendas. The first was the fight for constitutionalism against Abe Shinzo’s ideological politics and this was the political cause that linked opposition parties. The second was so-called identity politics, aiming to introduce an optional separate surname system for married couples and advance LGBT and other sexual minority rights. This became a symbolic agenda for opposition parties to differentiate themselves from the LDP. The third was social welfare policy. In contrast to the LDP, which uplifts households from above through economic growth, the CDPJ proposed welfare policies in which the government supports people’s livelihoods from below through social security.

Furthermore, the CDPJ and DPP both have a strong support base in Rengo (Japan Trade Union Confederation), which according to Nakakita Koji (professor at Hitotsubashi University) is a major advantage those two parties have over the JIP.

On the other hand, the political forces that occupies the position of the “reformists” have changed but are currently dominated by the JIP.

Osaka Restoration Association, a regional political party formed in 2010, has made its presence felt as “reformist” since entering national politics in 2012.

The JIP is sometimes regarded as the “friendly force of the LDP” by leftists and liberals on the basis of their affinity on the issues of constitutional amendment and nuclear sharing. However, we should not focus excessively on the hawkish aspects of the JIP because there are substantial differences between the JIP and the LDP when it comes to managing the administration.

Hashimoto Toru (former Governor of Osaka Prefecture, founder of Osaka Restoration Association) describes the antagonism between the JIP and the LDP in terms of “statics and dynamics.” In other words, the greatest source of political conflict in Japan today is whether to statically preserve the profit-dependent structures created between the government and businesses by the LDP under the 1955 System, or to disrupt those existing profit-dependent structures and dynamically mobilize the benefits provided by the government.

Based on this divergence within the broader conservative force, the JIP has the following distinctive policies.

The first is regulatory reform. The parasitic dependence of industry groups on the government in collusion with the LDP must be eradicated by “reformist” parties backed by the support of public opinion. The second is transparency and fairness in government. The revision of the existing restrictions on profit sharing was synonymous with establishing new, objective rules for the allocation of subsidies. The third is the reform of governance structure. The identity of the JIP was defined by reform of the administrative organization such as the Osaka Metropolis Plan (a plan to transform Osaka from a prefecture into a metropolis) and attempt to expand such administrative reform at the regional and national levels.

These “reformist” opposition parties regard those who do not belong to any organization and are outside the existing profit sharing system, namely, the independents, as their support base. According to Hashimoto, since 70 percent of voters do not belong to any industrial groups or labor unions and therefore cannot make their voice heard in the political arena, the “reformist” opposition parties had to incorporate those people as their supporters and embark on “dynamic politics” against the LDP.

Duality of “LDP dominance”

Whereas a centrifugal force separates the CDPJ from the JIP, the LDP is characterized by a two-sided nature that absorbs the policy stances of both.

The LDP contains some politicians who espouse deregulation and privatization, and they certainly share “reformist” politics with the JIP. In this respect, there is a strong affinity between former Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and the JIP.

This is evident in the words of Matsui Ichiro (former president of the JIP), who said, “The politician Suga can be summed up as a staunch reformist.” Considering the declining birthrate, aging population and voters’ aversion to the tax burden, administrative reform will be inevitable in the near future and “reformist” politics will continue to gain a certain amount of public support.

On the other hand, Abe Shinzo and the Abenomics economic policy have temporarily rendered invisible the conflict between neoliberal reform and the pork barrel politics that has split the LDP since the 1990s. The Abe administration finally even pursued “social democratic policies” such as the promotion of women’s participation and empowerment, and the demand for wage increases for workers. The COVID-19 pandemic required governments around the world to strengthen their administrative functions in terms of fiscal stimulus packages and the establishment of healthcare systems, then a “consensus” emerged in Japan that “big government” was accepted and expected. In response to this trend, in September 2021 Kishida Fumio urged “a shift away from the neoliberal policies that had been in place since the Koizumi Reform (by the Koizumi Junichiro administration, 2001–2006),” advocating a “New Form of Capitalism” that balances growth and distribution.

Overall, the LDP has both a “neoliberals (reformists)” side that responds to the demands of consumers and independents, and a “liberal (former progressives)” side that asserts the need to strengthen administrative functions when necessary. This flexible duality may have contributed to long-term stability of the LDP.

Necessary conditions for establishing regime change in the Heisei era

How is it possible to restore healthy political confrontation and competitive politics under the current “3:2:1” power relations of the opposition parties and the JIP against the LDP?

In order to investigate the conditions necessary for this to occur, I examine two regime changes that took place in the Heisei era (1989–2019), namely the Hosokawa Morihiro administration (1993–1994) and the DPJ administration (2009–2012).

The formation of the Hosokawa administration and the DPJ administration share four common elements.

The first is the leadership of the “non-LDP conservative reformists” who left the LDP, and the second is the organized backing of Rengo, which is the support base of the former progressives. These two elements may be considered the prerequisites for regime change in Heisei Japan. The third element is infighting and failure in the LDP, and the fourth element is favorable neutrality on the part of the JCP. When these elements coincided, regime change occurred in Heisei era.

In the case of the Hosokawa administration, the leadership of “reformists” who had left the LDP, such as Ozawa and Hata Tsutomu (1935–2017, former prime minister and co-founder of the JRP with Ozawa), formed a coalition framework that included Komeito and the SDPJ. Hosokawa Morihiro (former Governor of Kumamoto Prefecture, founder of the JNP, and former Prime Minister) was the essential player at the top, but it was Rengo that consistently backed the eight-party alliance. The Hosokawa administration may be said to have been the product of a compromise of two broad visions possible at that time: “two major conservative political parties” envisioned by Keidanren (Federation of Economic Organizations) and Rengo’s pursuit of an expanded “SDPJ, Komeito/Democratic Socialist Party line.”

The DPJ administration was also the result of a merger between politicians from the LDP, such as Hatoyama Yukio (former LDP member, who left the party and founded Sakigake; former Prime Minister) and Ozawa, and former progressives such as Kan Naoto and the SDPJ group. While the LDP in the post-Koizumi era lost its capacity to govern, the DPJ administration was a grand amalgam made by literally all political parties except the LDP and the JCP, and again it was the 7 million members of Rengo who systematically supported the administration.

In both of these regime changes, the moderate “reformists” and former progressives (liberals) came together and united all “non-LDP” and “non-JCP” political blocs, then Rengo backed these blocs, while the JCP remained neutral. Public opinion acknowledged this framework as an alternative political administration and entrusted government and diplomacy with their ballot. These were at least the necessary conditions for regime change in the Heisei era and the question was how to create this framework with a bottom-up process, with the approval and consent of all parties concerned. This fact offers a lesson for how the rivalry between the ruling and opposition parties can be revived.

Potential future regime change

Considering these historical conditions, how can the opposition parties make it possible to achieve regime change in the future? First, assuming a power relationship of “3:2:1,” a simple approach would be a “2+1=3,” which means combining the agendas of “liberals” and “reformists.”

This in no way implies a party union of the CDPJ and the JIP. Rather, a “2+1=3” approach means that the CDPJ would include more “reformists” oriented policies. In the Heisei era, “reformists” have steadily gained public support, which signifies there is a broad consent for “reform” in civil society. If the declining birthrate and aging population are given conditions, it is inevitable that the role of government will need to be redefined accordingly. These redefinitions will include the consolidation of public infrastructure, the revision of the allotted number of seats in the Diet, and the more dynamic regulatory reform. Opposition parties need to establish clear and consistent criteria regarding the role of the government, especially where it should expand or reduce its function.

The second approach would be to focus on “4,” which falls outside the power relationship of “3:2:1,” namely, the independents who are not affiliated with any particular political party, and to reintroduce these people into the political system again. The importance of this approach is all the more critical for opposition parties, because they have a less solid voter base than the LDP among organizations.

In light of the current low voter turnout rate, the election will naturally be decided by block votes of the industry groups of the LDP on the one hand, and the labor unions of the opposition parties on the other hand. An election campaign fought by an inner friend circle is said to fail, but the current election has in a sense become a campaign fought by an inner friend circle on a massive scale, namely the organized supporting base of ruling and opposition parties, potentially excluding the independents who have no ties with those intermediary groups. This will lead to a crisis for parliamentary democracy.

For opposition parties to compete on an equal footing with the LDP, they need to demonstrate the ingenuity and appeal necessary to create a bridge between labor unions and independents. Obviously, the policy interests of labor unions and independents may sometimes mutually conflict. Therefore, a policy package is required that recombines the interests of both parties at a higher level. Labor unions must be receptive to the demands of more workers, especially non-regular employees. At the same time, political parties must continue transforming themselves into “public instruments for the benefit of society,” strengthening their cooperative relationship with labor unions while developing their relevance to individuals who are not members of any organization.

Of course this is easier said than done. We are entering an era of increasing uncertainty, including a shrinking population and aging society domestically, as well as the decline of the United States and rise of authoritarianism internationally. However, what is certain is that only those who have the courage to reinvent themselves can adapt to the new era and survive the uncertain future.

Translated from “Tokushu Hi-hoshu toiu sentakushi: 1993 nen-taisei to ‘“3:2:1” no hosoku’—Seijiteki sentakushi no Kenzenna kikko no tameni (The alternative of non-conservatives: How can Japanese politics regain a competitive rivalry among political alternatives?),” Chuokoron, October 2022, pp. 30–37. (Courtesy of Chuokoron Shinsha) [November 2022].

Keywords

- Ohi Akai

- Hiroshima Institute of Technology

- politics

- 1993 System

- conservatives

- former progressives

- neoliberals

- LDP

- Komeito

- JIP

- opposition

- rule of 3:2:1

- LDP split

- non-LDP conservative reformists

- independent conservatives

- Heisei Democracy

- 1955 System

- regime change